Sunday, December 22, 2013

Nobody Here But Us Mongrels

(Picture from Io9's site here.)

I've been interested in Neanderthals for years.

The idea that there was a previous form of human being-- not quite like us but close enough to talk to-- that used to live essentially next door was irresistible.

My first accepted story involved a Neanderthal/Homo sapiens contact. And it came, as much of my fiction does, in retaliation.

I had just moved to Boston, fresh from the homogeneous midwest, and the amazing diversity stunned me. You could walk down a street in Boston and hear English in three different accents. Heck. You could walk down a street in Boston and hear three different languages. It was a different world.

Not surprisingly, I went to the science museum. At the time there was an exhibit on cave paintings. The docent was a well meaning old man who talked about the painters and how they couldn't possibly be painted by dumb old Neanderthals. This ticked me off and I went home and wrote a contact story from the Neanderthal point of view about encountering those smelly idiots, Homo sapiens. Asimov's bought it and I was off.

It turns out I was right.

Not about the cave paintings. Those are clearly dated and post-date when Neanderthals were in Europe. Not to say they didn't paint things or paint in caves. We don't know and, frankly, it's unlikely we ever will. But I was right in that Neanderthals were a whole lot smarter and like us than some thought way back in the Cretaceous-- that is, when I moved to Boston.

This idea that not only Neanderthals but most of our early relatives have been miscast has been growing over the years. A number of very important stories broke in just the last year.

The stuff that's mostly been in the news has been genetic in origin. One of the earliest discoveries was how some modern humans shared DNA with Neanderthals in such a way as to suggest cross breeding. What made it especially interesting was that the distribution of the Neanderthal DNA was not uniform. Some groups got more than others.

Then came the Denisovans, a group of fossils discovered in Siberia. Those fossils were about 41k years old Sequencing the Denisovan DNA suggested more interbreeding. More Europeans had Neanderthal than other groups. More Asian and folks from Oceania had Denisovan DNA. This suggested interbreeding might be a local affair. After all, Neanderthals were mostly in the mideast and up into Europe while Denisovans were more in Asia.

Then the Denisovans were compared with Neanderthals. Sure enough, there was interbreeding there, too. In point of fact, there was evidence that there was interbreeding between Denisovans and a potentially unknown hominin.

It shouldn't come as any surprise that humans will pretty much have sex with anything. Any perusal of a porn site will demonstrate that pretty adequately. Or you can read this in Scientific American. But go with an open mind.

That lack of surprise should therefore lead to a lack of surprise that we interbred with those previous cultures had considered, well, beasts. We're starting to look at our cousins as more and more like ourselves. Different, to be sure. There are a lot of differences, too. For one thing, your average run of the mill could toss your top star line backer over the goal posts. There appears to be a fairly vast difference in potential strength between our two groups. It also looks like Neanderthals had a different way of speaking and, potentially, seeing. They were different.

But not, apparently, different enough not to be taken seriously persons of affection.

This has caused several anthropologists and archaeology to rethink the whole idea of what species we all might be to one another. There are species fundamentalists that believe that if two individuals can interbreed they are, by definition, the same species. By that definition, none of these folks are separate species at all.

But it gets even more interesting.

Let us travel to Dmanisi, Georgia.

The Dmanisi site is quite old-- 1.8 million years old. Five skulls have been found. All skulls have been dated to a similar time frame. All are quite different-- not different enough to be unrelated, mind you. The variation between the five skulls is similar to variation between random skulls of humans or chimps. But different enough that if they had not been found together they might have been considered different species. John Hawks has a good discussion of the Dmanisi skull here.

One of the interesting things Hawks mentions is that the most human like skulls were adolescents while the adult skulls in the same site had significantly reduced brain case sizes.

This is an interesting indicator to me. We know that we have bigger brains than our distant ancestors. That requires two things: variation in brain size and selection pressure in favor of larger brains. A mechanism might be nice. Possibly the mechanism for this is our lengthening childhood. We end up not selecting directly for big brains but for the variation in lengthening time as juveniles which give us the opportunity to develop sufficient brains to make a selective difference. Be interesting to see if that shows up in future science.

Be that as it may, it appears that diversity in the human species may well be the name of the game. Instead of differing species (Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, Homo sapiens) there is one human species for the last ~2 million years with lots of variation. We're an experimental species. It's interesting to note a symmetry between our biological heritage and our proclivities.

One thing Hawks says and I believe it is true. He says that recent humans are not a good measure of our history. We're now pretty much the only game in town. All of our cousins are either dead or absorbed. We like to believe that we're still the same as we ever were: now, a hundred years ago, a thousand years ago. Maybe that's true. Or maybe that's just the conceited present thumbing its nose to the silent past.

A hundred thousand years ago we were not alone. There were other intelligent eyes peering out of big brained skulls seeing things differently from us.

I'd guess from the genetic evidence we found that pretty attractive.

Further links:

Nature

A. P. Van Arsdale

Early stone tipped projectiles, here and here

Mystery human species

Pushing back the clock on human finds

Sunday, December 1, 2013

Stumbling on the Edge of Magnificence

(Picture from here.)

There is a lot to be excited about in science lately. Too much for me to have an entire post devoted to one thing. So here's a quick overview of some fun things.

There is new evidence that humans were in the Americas as far back as 30,000 years ago. This comes from a cave full of giant sloth bones found in Uruguay. There's been some evidence before (cited in the article) but this is even more of it. For a long time now there's been cracks in the idea that humans came over from Siberia via the Bering land bridge not much more than 13,000 years ago-- the Clovis people, named after the spearpoints found in Clovis, New Mexico. The researchers in Uruguay think that theseinhabitants may have come over from Africa. A sequence of the genome of a 24,000 year old Siberian body has suggested that there are Eurasian relatives to the Native Americans, further complicating the puzzle.

New Lithium-Sulfur batteries might actually solve the power storage problem of renewable energy. This has been something I've been following over the last few years. Lithium-ion batteries are expensive and don't have the energy density to be really practical for things like cars. But Li-S batteries are a different story. They have significantly better energy density. But they start to fail after a small number of charges. This new research might solve that issue.

There is a spacecraft from India making its way to Mars. Mangalyaan is going to look for methan. Of course, there are people who are upset that India, with its widespread poverty, is going to put its money into a Mars mission. Probably the same people who don't like it that we put a minuscule amount of money into looking at Saturn because we have poor people in Arkansas. To heck with them. Go India.

China is getting ready to launch a rover to the moon today. The moon will Chinese someday. I'm certain of it.This may not be a bad thing.

A 4.4 billion meteorite uncovered by Bedouins looks to be a relic of the ancient Martian crust. Part of the conclusions from studying this meteorite's composition is that Mars was not hit by an ancient planetoid a long time ago. But if that's true they're going to have to come up with a different explanation for Mars' weird shape.

One of the new potential uses for graphene is to be used in the manufacture of condoms. Better condoms means more condom use. Graphene enhanced condoms will feel better, be stronger and, hopefully, lasts longer in the wallet.

The ISS has launched a tiny satellite into orbit. The satellite is about 12"x4"x4" and weighs about 5 pounds. The satellite is intended to test a new de-orbit technique known as an "exo-parachute." The article doesn't say how the satellite was launched. One wonders if one of the astronauts just threw it out the window.

There's a puzzle at the heart of nuclear physics. If you measure the diameter of a proton by one method set you get an answer. If you measure it by a different method you get a completely different method. One researcher has suggested that this my be due to quantum gravity. The first method set is two fold. First by using energy levels derived from hydrogen spectroscopy. Second by electron scattering. Both of these get an answer of about 0.88 femtometers. But in 2010, scientists tried experiments using a muon (a negatively charger particle about 200 times the mass of an electron) instead of an electron. They got 0.842 femtometers. That's a big difference. One researcher is suggesting the difference is due to the muon's greater mass. He suggests that the weak attractive force between the nucleus and the electron-equivalent is actually the quantum representation of gravity at the small scale. If so, it's a big leap towards the unified field theory.

Finally, everybody knows crows are smart. Some have likened them to primates on the wing. New neurobiology research has given some insight into how they're that smart. After all, birds do not have a neocortex like mammals-- it developed after we split off from the line that developed into birds. In addition, whatever crows are using to be smart it's operating in a fraction of the size of a mammalian brain. A crow's brain isn't much bigger than your thumbnail.

They appear to use a structure called the nidopallium caudolaterale, a collection of nerve cells in the back of the bird brain. This article suggests that though the structure is embryologically completely different from the pre-frontal cortex of the mammalian brain, it may function similarly. This might mean a common underlying neurobiological basis of intelligence.

The above said, I find myself a little discouraged. I love science. Part of science, though, is science funding and that is getting more scarce as time goes on. Being an American I'd like my country to be in the forefront of scientific research-- and it is, in general. But if you analyze the funding of science in my country (See here.) the amount going to fundamental and basic research is getting less over time, not more. Most of the funding for research and development is in the development side of things and most of everything is defense related.

We have the tools for the first time in human history to understand the fundamental operations of the natural world. We've started to unlock the primary mechanisms of life, of physics, of our planet and the cosmos. We are learning every year more than we ever knew before.

It's disturbing to me that when such wonderful things are going on, when we are within visible targets of solving most of the world's technological problems such as disease, energy, food production and even climate change, we short change ourselves.

I am not saying we're going to solve these issues tomorrow. But how can we hope to have a healthy world when pharmaceutical companies stop antibiotic research and don't put much in the pipeline to replace it? How can we study the natural world when we pave over it? How can we mitigate climate change when we deny it's happening?

Perhaps there's a new form of natural selection at work, where our species is being tested whether or not we will stumble on the edge of magnificence.

Sunday, November 17, 2013

Writing: Code vs. Cipher

I don't have many favorite works. Things that percolate up to favored status are usually too different to be easily compared. For graphic novels, would I prefer Kingdom Come or V for Vendetta. How to compare The Stars My Destination or The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch?

But I do have a favorite poem: Ars Poetica by Archibald MacLeish.

I've read a lot of MacLeish and Ars Poetica is not his strongest piece-- for my money, that would be J. B., his verse play about Job. But the poem speaks to me about something I find important: how writing works.

I think of language is a code not a cipher. This is an important distinction. A cipher is a regular algorithm by which data can be encrypted or decrypted. Classical ciphers often used some algorithmic means by which words or letters were substituted. A very simple cipher might be to substitute the number placement of a letter for the letter. "ABCDE" becomes "12345", etc. "HELLO" would be "8-5-12-12-15".

A code, on the other hand, is a method of obscuring the original intent. It usually requires a key. For example, say you and I agree that the word "yellow" in a message means meet me at midnight under the harvest moon. If someone intercepts that message they have no idea what it means. There is no computational algorithm that can be used to determine yellow's meaning.

But the difference between a cipher and code is deeper. Philosophically, a cipher indicates that there is some rule set that can be applied to make the obscure open to scrutiny. A code, on the other hand, is an agreed upon communication protocol between two (or more) thinking beings.

Language is a tokenized communication protocol where something deeply personal and obscure (thoughts, eelings) are communicated one person to another via tokens for which we have some measure of agreement on their meaning. It is a code and not a cipher.

Writing a story is setting up a collection of words and images that are designed to invoke a response in the reader. Writers are encoding a state into words and expecting it to be decoded into emotions and narrative on the other side.

Cipher-thinking is deliberating on a set of rules and believing they will achieve an outcome. It's akin to magical thinking. You dance this way and that, turn three times, bay at the moon and bathe in the blood of a chicken and lo: you will have a best seller.

It can certainly work. There have been any number of pop songs and hack novels written strictly to formula without any other distinguishing mark.

Code thinking, however, is completely different. It recognizes that (minus telepathy) there is no possible algorithm by which we can express our innermost thoughts and feelings. We must mediate such communication through the inadequate tokens of words. Consequently, we introduce ambiguity and mistakes along with broader meaning. It means we do not present but invoke.

Back to MacLeish. Ars Poetica was written in 1925. T. S. Eliot's The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock was written in 1920. I find a lot of common ground in both of these poems. Prufrock seems to me a lament against the victory of form over substance. (An interesting side note, let us not forget Artaud's famous quote from The Theater and Its Double, 1938: "And if there is still one hellish, truly accursed thing in our time, it is artistic dallying with forms, instead of being like victims burnt at the stake, signalling through the flames.")

MacLeish, on the other hand, doesn't lament about it at all. He just tells us how it is done. One of my favorite lines in the poem: "A poem should be equal to. Not true."

Too often we indulge in cipher thinking. If I do this, I'll get that. If I love my wife I'll be happy. If I'm good to my kids, they'll turn out right. If I do what my parents ask, they'll approve of me. Cipher thinking is contractual. Life (and writing) are not contracts but agreements. We agree that I will give you the best effort at a story that I can. No guarantee can be made that you'll like it.

Of course, MacLeish said it much better:

But I do have a favorite poem: Ars Poetica by Archibald MacLeish.

I've read a lot of MacLeish and Ars Poetica is not his strongest piece-- for my money, that would be J. B., his verse play about Job. But the poem speaks to me about something I find important: how writing works.

I think of language is a code not a cipher. This is an important distinction. A cipher is a regular algorithm by which data can be encrypted or decrypted. Classical ciphers often used some algorithmic means by which words or letters were substituted. A very simple cipher might be to substitute the number placement of a letter for the letter. "ABCDE" becomes "12345", etc. "HELLO" would be "8-5-12-12-15".

A code, on the other hand, is a method of obscuring the original intent. It usually requires a key. For example, say you and I agree that the word "yellow" in a message means meet me at midnight under the harvest moon. If someone intercepts that message they have no idea what it means. There is no computational algorithm that can be used to determine yellow's meaning.

But the difference between a cipher and code is deeper. Philosophically, a cipher indicates that there is some rule set that can be applied to make the obscure open to scrutiny. A code, on the other hand, is an agreed upon communication protocol between two (or more) thinking beings.

Language is a tokenized communication protocol where something deeply personal and obscure (thoughts, eelings) are communicated one person to another via tokens for which we have some measure of agreement on their meaning. It is a code and not a cipher.

Writing a story is setting up a collection of words and images that are designed to invoke a response in the reader. Writers are encoding a state into words and expecting it to be decoded into emotions and narrative on the other side.

Cipher-thinking is deliberating on a set of rules and believing they will achieve an outcome. It's akin to magical thinking. You dance this way and that, turn three times, bay at the moon and bathe in the blood of a chicken and lo: you will have a best seller.

It can certainly work. There have been any number of pop songs and hack novels written strictly to formula without any other distinguishing mark.

Code thinking, however, is completely different. It recognizes that (minus telepathy) there is no possible algorithm by which we can express our innermost thoughts and feelings. We must mediate such communication through the inadequate tokens of words. Consequently, we introduce ambiguity and mistakes along with broader meaning. It means we do not present but invoke.

Back to MacLeish. Ars Poetica was written in 1925. T. S. Eliot's The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock was written in 1920. I find a lot of common ground in both of these poems. Prufrock seems to me a lament against the victory of form over substance. (An interesting side note, let us not forget Artaud's famous quote from The Theater and Its Double, 1938: "And if there is still one hellish, truly accursed thing in our time, it is artistic dallying with forms, instead of being like victims burnt at the stake, signalling through the flames.")

MacLeish, on the other hand, doesn't lament about it at all. He just tells us how it is done. One of my favorite lines in the poem: "A poem should be equal to. Not true."

Too often we indulge in cipher thinking. If I do this, I'll get that. If I love my wife I'll be happy. If I'm good to my kids, they'll turn out right. If I do what my parents ask, they'll approve of me. Cipher thinking is contractual. Life (and writing) are not contracts but agreements. We agree that I will give you the best effort at a story that I can. No guarantee can be made that you'll like it.

Of course, MacLeish said it much better:

A poem should not mean

But be

Sunday, November 3, 2013

Harvest Time 2013

I've been a little discouraged about things lately what with government shutdowns and such. There's been a lot of good science coming out but it's been overshadowed by the news. Wendy commiserated with me somewhat but finally said: just blog about something that's not discouraging.

She is, as usual, right.

I like this time of year. We do a lot with the patch of land we have and have many ambitions and ideas and experiments we plan over the winter and put into practice in the spring. Then, in the fall, we see what we were able to do, what worked, what didn't and start making plans for next year.

Essentially, we try to do four things with the land: wood, garden, orchard and chickens.

The wood we use for heating and, if I can find some good stuff, turning in the shop. It was a good year for firewood. We dropped a hickory and a maple and so we're good for firewood for a couple of years. There might be some turning maple there, too. I've left some large blocks to season over the winter. We'll see what we have in the fall.

I don't do much turning. It's fun but mostly it's a way to make shavings. But it's fun. Mostly, I repair and build things for the household. Actually, this year the major shop project was the shop. I tore down a wall and replaced the workbench with a pair of workbench tables. It's been a lot of work. Today I finished putting the electricity back in. Hopefully, I can get the shop back into working order pretty soon.

What I'd really like to do is build musical instruments. But that had to take a back seat a while back for all of the other work we've been doing on the land. It didn't help that work moved to Cambridge and added in a ninety-minute commute. As most of it is by train and I can write it's not too onerous. But it does take a hit. I'm hoping to get back to it this winter. I have a mandolin I'd like to build. And a banjo. We will see.

The garden went well. Lots of summer material like squash and greens. Not much in the way of watermelons. I'm an optimist, I suppose. I believe I can grow melons in New England. But it did happen one year. The summer my son was born was also the first year we were successful in growing melons. Very tasty.

We have several ground fruits we're working with. We have a new strawberry bet that we have high hopes for next year. The thornless black berries we planted last year started bearing this year. Next year we should have some real harvest on it.

We put in a few new raised beds for more garlic and shallots. This year we had three seven foot strings of shallots and we're working through them. Not enough garlic. We need at least as much. Next year.

I redid the grape arbors this year. We have five. Three did well. Two, not so much. The marechal foch grapes were vigorous but spotty. We've had strange weather the last few years with heat early, a wet and cold June and then mixed the rest of the summer. The MF grapes came in at different times. In part this is because the MF vine has gotten huge. I let it wander the fence of the garden and it now spans about thirty feet-- long enough that the microclimate of one end is different from the microclimate at the other. I'm going to have to retrim it.l The Concords did all right but I rebuilt their arbor and they didn't like it.

We have a battle brewing on one arbor between a seeded table grape and a seedless table grape. The seeded one is winning. I can't have that-- I like the seedless better. So I'll transplant the seeded somewhere.

The grapes at the bottom of the hill are next to the road. They didn't do well this summer. I may have to rethink them.

We didn't harvest the elderberries this year. The plants didn't look happy enough and there wasn't much so we let the birds have them.

We planted kiwi on one of the fences a couple of years ago and Ye Gods! has it taken off. It is threatening to rip the fence apart. So yet another transplant.

The orchard-- well, let's be a bit more particular. The fruit trees. The word "orchard" conjures up a hill with gnarled trees growing on it. We don't have that much land. I do have some espaliers I've built and one Belgian fence. The espaliers have cherries. Cornelian cherries, apples and plums on them. There's a medlar as well but it will be a while before I have that sorted out.

We're trying all sorts of things on the Belgian fence. Crabapples, of course, but also a few quinces, a peach, a couple of pears, a couple of pecans, some filberts and a mulberry. The peach was an experiment for a tree that wasn't doing well so I just put it in a pot. It seemed to recover so I planted it on the fence. The top died off and some sort of peach family is coming up from the roots. We'll see what happens.

The filberts have gone nuts. They threaten everything else so they must be moved. Ditto the mulberry.

The pecans haven't done so well with the fence so I'll put them behind the greenhouse. Maybe I'll live to see pecans. Maybe not. Maybe Ben will see them if he decides to keep the house.

Good harvest on the Cornelian cherries and the pie cherries. The crab apples have done so-so. One crab apple produces a good supply every year but the others have not. Essentially, this is true for all our apples. I know one problem we have-- a worm that attacks the blossoms. We have to spray early and keep spraying until the blossoms fall. That works to start the fruit. But I've noticed that no other apple tree in the neighborhood has this problem so I think it's an effect rather than a cause. I think I'm pruning them badly. This winter I'm going to spring for a professional and then leech his brain.

We're having trouble with our sweet cherries. We get cherries but they're almost immediately bit and then covered with fuzz. We have a similar problem with plums. We're not terribly excited with spraying-- we do use Surround, a sort of Kaolin clay product. That works for fruit that can tolerate the first insect bite. This includes grapes, apples, pears, peaches, etc. But apparently plums and cherries don't manage it.

Which brings us to the rest of the outdoor fruit trees. We have guomis, peaches, nectarines, almonds, apricots, cherries, honeyberries, aronias and apples. Apples and cherries I already mentioned.

The guomis are eat-while-it's-there fruit. We've never

Good harvest on the peach tree-- we've been thinking it was getting old every year and every year it gives us a good harvest.

Not so much on the nectarines. We had a good crop but they got a fungus and it ate back at part of the tree. Not good. Not good at all. I'll spray it this winter with a strong fungicide and see how it does in the spring.

The honeyberries are hit or miss. We have two plants. One tastes pretty good but I don't like the other one. They have gotten a little out of control and need to be cut back. Again, we let the birds have them. We may rip them out entirely. Ditto the aronia-- I think they need to be moved.

Very good harvest in the greenhouse. Many guavas. A few pineapples and many tens of pounds of bananas. Oh, and many chestnuts.

The chickens were good this year. We lost Sam, our old rooster. After a decade he decided it was time to try for a new karmic level. We have a new rooster I call Fish. Not sure exactly why but he reminds me of a fish. He's settling in. The hens are all getting on. We're getting good egg production but it's been going down hill. Maybe next year we'll hatch up some eggs and keep a couple of the hens. Sell the remaining hens and grow up the roosters for the oven.

When we first did this we had a half dozen roosters and Wendy didn't think she could manage to harvest them. But the month after they started to crow she let on that maybe she could manage after all.

So, all in all, a fairly good year.

What to plan next year?

Dropping the two trees opened up a section of the yard that is begging to become a tiny orchard. A real orchard, this time. So we're looking at trees. I've learned something though in the last few years. Get stock that fruits quickly. No more waiting ten years for a harvest.

Many of the trees will be moved. The aronia, mulberry, filberts and pecans. I'm hopeful we'll get something good by 2015.

Next year we want to try to scale up production. Get enough beans from the garden to last the winter. Potatoes and other staples as well. We grew good mill corn a couple of years ago. The big problem is storage. Wendy wants me to make a root cellar of some sort. Maybe I will.

Get the grapes back on line-- I was able to make wine this year but it was mostly from the grapes of previous years. A hundred pounds of apples dropped in our laps this weekend and we're scrambling to process them all. So that's a major learning experience. If the pruning of the apples works, next year we might have that problem from our own trees.

I have to get that fungus problem under control. Not sure how to do that.

The chestnuts are finally coming on line. We got about five pounds so far this year. Not much but it's a start. Ditto the almonds-- only about twenty. But the tree is still young.

Wendy worries about having too big a harvest to handle. I figure that's a problem I'd like to learn to overcome.

Sunday, October 20, 2013

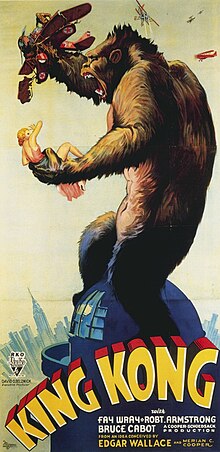

Consideration of Works Past: King Kong

King Kong has been a staple in media for a long time. I'm not sure what sort of genre to put something like King Kong. SF? Fantasy? Paranormal romance? It's certainly the first of the Kaiju sort of films but it's not, really. Kaijus are monsters. They look either robotic, reptilian or alien. Kong is striking precisely because he's nearly human.

The original Kong was an invention by Merian C. Cooper in his film, King Kong (1933). It was remade by Dino De Laurentis in 1976. And remade again in 2005 by none other than Peter Jackson. Toho Films got into the act pitting him against Godzilla. Call him Kaiju Kong.

There's also been a musical.

Son of Kong was released the same year as King Kong. It's a sequel where Skull Island where Kong was originally found is revisited. They find a baby Kong and it saves them when the island sinks beneath the waves. Cooper apparently didn't have much to do with the sequel.

Mighty Joe Young came out in 1949. This one was written and directed by Merian Cooper.

Pretty much everyone knows the story: Carl Denham decides to go on a dangerous expedition for a new and exciting subject matter for a film-- he's famous for making animal pictures. He finds Ann Darrow in New York to be his leading lady. They board a ship looking for parts unknown. Jack Driscoll, first mate on the ship, becomes Ann Darrow's love interest.

Eventually, they reach Skull Island where they find African derived natives that lose no time sacrificing Darrow to appease the creature Kong, a ten story tall gorilla. Kong takes her off into the jungle and the crew go off to rescue her. Kong's not the only big thing on the island. Dinosaurs, giant insects and lots of other things are there but, eventually they manage to capture Kong alive and take him back to New York. They're able to do this largely because Kong has developed an attachment to Darrow.

In New York, Denham puts Kong on display. He gets loose and looks for Darrow, finds her. Can't really escape but climbs the Empire State Building, is shot by airplanes and falls to his death. Darrow survives and Denham utters his famous line: it was beauty that slew the beast.

I came back to this film by way of the Jackson remake. I took my son to it when he was probably too young to see it-- eight. Jackson, I think, really went to the heart of the original film. The plot is essentially the same. Driscoll is now the screen writer. Darrow is a plucky tough girl and not the swooning screamer she was in Cooper's film. Kong is really the star, though. He's smart, lonely, scarred and incredibly ancient. Jackson took on the natives as terrifying and strong so that when we see dancers in New York imitating them, it's clearly tamed down. It underlies what Denham is trying to do to Kong. He's trying to reduce him in stature to fit within the civilized world.

But Kong still dies.

This disturbed Ben no end. He asked that I write a story where Kong lived. I did so and that made him feel better.

It got me to thinking. King Kong, in all it's remakes, is essentially a romance. Kong dies as a romantic event in the same way the Romeo and Juliet die at the end of the play. Death in a romantic film is the fulfillment of the romantic arc. Kong meets girl. Kong loses girl. Kong dies.

I have a lot of trouble with romances. As far as I'm concerned the story stops when it's just getting interesting. Romeo and Juliet essentially stops with the death of the lovers. But I want to know how the two families adjust to the lost.

Similarly, in Kong, the relationships forged in the film are fulfilled by the death of Kong. Driscoll and Darrow are together (or seem to be) united in grief over Kong. Denham has had some sort of epiphany but it's not clear what it is. And there's about fifty tons of raw, steaming meat at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street.

Heck. Things are just getting interesting.

I think Cooper was getting at this when he wrote Mighty Joe Young. The original MJY has some real problems, though not as many as the remake in 1998. In this film, again a filmmaker goes into the bush to find subject matter and meets Jill Young and her adopted "brother", Joe: a twenty foot tall gorilla. She is persuaded to bring Joe to New York but they are miserable and ultimately escape back to Africa. The point here is that Joe lives. He goes on to fulfill his relationships with Jill and her new husband Gregg. The implication is that life is a continuing process. It doesn't stop just because the main character dies or gets married or divorced. It goes on.

This is the tack I took on the story I wrote for Ben.

Taking a non-romantic view of Kong opened up a bunch of interesting possibilities. Kong lived on Skull Island, populated with dangerous, wonderful creatures. The very instant Kong is made public there are about forty scientific expeditions shipping east. The discoveries found there would shake the world. What would the discovery and fascination with giant gorillas do to the image of gorillas world wide? Would poaching become ubiquitous and gorillas shortly become extinct and then viewed only as dismembered curios? Or would the there be love for Kong? Enough to protect gorillas forever?

Or who is in that audience on that fateful night? Margaret Meade? Kermit Roosevelt? What would Kong mean to gorilla researchers and conservationists in the future? To Dianne Fossey? To Jane Goodall?

If Kong wasn't going to die, what would happen to him? He was the last of his kind-- I took his attachment to Darrow not as a last gasp of his life but a late reaching out for hope. Kong knew he was the last of his kind. Bonding with Darrow was an act of acceptance that his life would go on anyway. He wasn't going to commit a noble sacrifice or seek an honorable death. He wanted to live. Death was inevitable but Kong would meet it on his terms and in his own time.

I read the story to Ben and it seemed to alleviate many of the issues the film and dropped the story in a drawer for a while.

But it wasn't quite realized and to me leaving an unrealized story in a drawer is like eating only one peanut. After all, they sit in their bowl and just glow at you. Eat me. Come one. It'll be good.

So after a couple of years I rewrote the story as a real story-- probably a thankless task since I can't publish it because of copyright restrictions. But I still wanted to:

It's told as extracts of books and articles by the principle characters looking back on everything that happened to them because of Kong. After all, this was the most important encounter in their lives. The principle characterss were changed but the world is, too. Dianne Fossey was not killed by poachers but runs the Karisoke Research Center and Preserve, funded in part by Carl Denham. Poaching is anathema all over Africa.

Kong died of old age in 1966, living on a large farm in Iowa with Jack and Ann Driscoll. The Kong Room in the American Museum of Natural History is dedicated to his memory.

The original Kong was an invention by Merian C. Cooper in his film, King Kong (1933). It was remade by Dino De Laurentis in 1976. And remade again in 2005 by none other than Peter Jackson. Toho Films got into the act pitting him against Godzilla. Call him Kaiju Kong.

There's also been a musical.

Son of Kong was released the same year as King Kong. It's a sequel where Skull Island where Kong was originally found is revisited. They find a baby Kong and it saves them when the island sinks beneath the waves. Cooper apparently didn't have much to do with the sequel.

Mighty Joe Young came out in 1949. This one was written and directed by Merian Cooper.

Pretty much everyone knows the story: Carl Denham decides to go on a dangerous expedition for a new and exciting subject matter for a film-- he's famous for making animal pictures. He finds Ann Darrow in New York to be his leading lady. They board a ship looking for parts unknown. Jack Driscoll, first mate on the ship, becomes Ann Darrow's love interest.

Eventually, they reach Skull Island where they find African derived natives that lose no time sacrificing Darrow to appease the creature Kong, a ten story tall gorilla. Kong takes her off into the jungle and the crew go off to rescue her. Kong's not the only big thing on the island. Dinosaurs, giant insects and lots of other things are there but, eventually they manage to capture Kong alive and take him back to New York. They're able to do this largely because Kong has developed an attachment to Darrow.

In New York, Denham puts Kong on display. He gets loose and looks for Darrow, finds her. Can't really escape but climbs the Empire State Building, is shot by airplanes and falls to his death. Darrow survives and Denham utters his famous line: it was beauty that slew the beast.

I came back to this film by way of the Jackson remake. I took my son to it when he was probably too young to see it-- eight. Jackson, I think, really went to the heart of the original film. The plot is essentially the same. Driscoll is now the screen writer. Darrow is a plucky tough girl and not the swooning screamer she was in Cooper's film. Kong is really the star, though. He's smart, lonely, scarred and incredibly ancient. Jackson took on the natives as terrifying and strong so that when we see dancers in New York imitating them, it's clearly tamed down. It underlies what Denham is trying to do to Kong. He's trying to reduce him in stature to fit within the civilized world.

But Kong still dies.

This disturbed Ben no end. He asked that I write a story where Kong lived. I did so and that made him feel better.

It got me to thinking. King Kong, in all it's remakes, is essentially a romance. Kong dies as a romantic event in the same way the Romeo and Juliet die at the end of the play. Death in a romantic film is the fulfillment of the romantic arc. Kong meets girl. Kong loses girl. Kong dies.

I have a lot of trouble with romances. As far as I'm concerned the story stops when it's just getting interesting. Romeo and Juliet essentially stops with the death of the lovers. But I want to know how the two families adjust to the lost.

Similarly, in Kong, the relationships forged in the film are fulfilled by the death of Kong. Driscoll and Darrow are together (or seem to be) united in grief over Kong. Denham has had some sort of epiphany but it's not clear what it is. And there's about fifty tons of raw, steaming meat at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street.

Heck. Things are just getting interesting.

I think Cooper was getting at this when he wrote Mighty Joe Young. The original MJY has some real problems, though not as many as the remake in 1998. In this film, again a filmmaker goes into the bush to find subject matter and meets Jill Young and her adopted "brother", Joe: a twenty foot tall gorilla. She is persuaded to bring Joe to New York but they are miserable and ultimately escape back to Africa. The point here is that Joe lives. He goes on to fulfill his relationships with Jill and her new husband Gregg. The implication is that life is a continuing process. It doesn't stop just because the main character dies or gets married or divorced. It goes on.

This is the tack I took on the story I wrote for Ben.

Taking a non-romantic view of Kong opened up a bunch of interesting possibilities. Kong lived on Skull Island, populated with dangerous, wonderful creatures. The very instant Kong is made public there are about forty scientific expeditions shipping east. The discoveries found there would shake the world. What would the discovery and fascination with giant gorillas do to the image of gorillas world wide? Would poaching become ubiquitous and gorillas shortly become extinct and then viewed only as dismembered curios? Or would the there be love for Kong? Enough to protect gorillas forever?

Or who is in that audience on that fateful night? Margaret Meade? Kermit Roosevelt? What would Kong mean to gorilla researchers and conservationists in the future? To Dianne Fossey? To Jane Goodall?

If Kong wasn't going to die, what would happen to him? He was the last of his kind-- I took his attachment to Darrow not as a last gasp of his life but a late reaching out for hope. Kong knew he was the last of his kind. Bonding with Darrow was an act of acceptance that his life would go on anyway. He wasn't going to commit a noble sacrifice or seek an honorable death. He wanted to live. Death was inevitable but Kong would meet it on his terms and in his own time.

I read the story to Ben and it seemed to alleviate many of the issues the film and dropped the story in a drawer for a while.

But it wasn't quite realized and to me leaving an unrealized story in a drawer is like eating only one peanut. After all, they sit in their bowl and just glow at you. Eat me. Come one. It'll be good.

So after a couple of years I rewrote the story as a real story-- probably a thankless task since I can't publish it because of copyright restrictions. But I still wanted to:

It's told as extracts of books and articles by the principle characters looking back on everything that happened to them because of Kong. After all, this was the most important encounter in their lives. The principle characterss were changed but the world is, too. Dianne Fossey was not killed by poachers but runs the Karisoke Research Center and Preserve, funded in part by Carl Denham. Poaching is anathema all over Africa.

Kong died of old age in 1966, living on a large farm in Iowa with Jack and Ann Driscoll. The Kong Room in the American Museum of Natural History is dedicated to his memory.

Sunday, September 22, 2013

Consideration of Works Past: The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

(Picture from here.)

I am now and have always been your friend-- oops. Wait. Got my wires crossed.

I am now and have always been a Phillip K. Dick fan.

I've pretty much read most of what he's written-- there may be a couple of novels I haven't managed to connect with and perhaps a few stories in the compleat works I haven't gotten to. He had a pretty sizable body of work.

I think of PKD work the same way I think of zen koans and parables. The parables I've read go something like this. The story: goes fairly normally-- a pilgrim looking for an answer to a question or some such-- until a particular point where the narrative bends such that the reader must flounder. It's analogous to the story systematically building the reader a beach and inviting him on a walk only to discover it's quicksand. The intent of the work is to challenge the reader into a new path.

A good example of this sort of thing is Dick's The Man Who Japed. Japed is the story of a Calvinist-inspired world following an apocalypse. A mediocre writer might do a "One man against the world" sort of thing. But this denies that there is actual value in strict morality. Dick created a character who is a creative artist, a misfit in the society who is nonetheless very successful, and believes strongly in a strict morality. He does bring the society to task-- sort of. And he does it with a sense of humor. Not war but laughter.

See? Zen koan.

Eldritch is a much more serious work than Japed. Like all Dick novels it starts with a businessman. In this case, a man with precognition employed by a company that uses his ability to detect what products will be in fashion and what products will remain unsold. This is at the very heart of a Dick novel-- they always start with something we would call mundane. In Doctor Bloodmoney it's a TV salesman. In Japed it's a man who is running a media production house. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep it's breakfast between a husband and wife. The husband is a cop. Only later do you discover he's a bounty hunter who's job it is to destroy escaped androids.

The book largely concerns itself with Barney Mayerson-- the precog mentioned above-- and his boss, Leo Bulero. Bulero has been force-evolved to have a higher brain function. Their company produces Perky Pat layouts: a miniature model system that is the focal point for users of an illegal drug, Can-D. Users of Can-D are able to unite in the form of characters on the layout. Can-D is illegal on earth but freely available on the colony planets of Mars and Venus. In point of fact, Mars and Venus are so hostile that colonists are psychologically unable to cope with living there without Can-D.

Into this volatile situation comes Palmer Eldritch, a charismatic businessman who had gone to Proxima Centauri years before and has now returned. Returned with Chew-Z, a competitor drug to Can-D.

Now, a mediocre writer might turn this into a drug war. Or make some obvious moral distinction. But taking drugs is not a moral problem in this book. Why you take them, or why they're sold to you and what are the moral and psychological consequences of those decisions is that book's target. Is Can-D a religious experience? Is Chew-Z? If they are, what is the meaning of two different and competing religious experiences? What is the nature of reality but the perception and if these drugs change perception (which they profoundly do) is that not any less real than the sober experience? What is the difference between a religious experience mediated by a drug and one mediated by the church? Is there a difference?

Dick doesn't just tell you one way or the other. His characters wrestle with these questions. Some wrestle weakly. Others do a pile driver on them. There is sin and redemption in this novel and the nature of what constitutes a sin and what constitutes a redemption.

I first ran into this novel (and subsequent Dick) in Alabama in the late sixties. When I first picked it up I suddenly realized that up to that point I had been reading SF with children in the starring role. Think about it. Most SF and fantasy arcs are coming of age stories. One man against the world. Lost prince stories. Chosen ones. Fulfilling of prophecies. Fights against the father. These are all adolescent boy stories-- regardless of the gender of the main character.

That's not to say you can't make a brilliant work out of a Bildungsroman-- Hell, that's half of mythology. But it is at the end a story about a boy becoming a man. Which means for a good portion of the story the protagonist is a child with childish things.

Every character in a Dick novel is an adult. Sometimes even the kids. By this I mean they are already fully formed members of society and are no longer dealing with the process of becoming members of society but are now dealing with the consequences and obligations of being members of that society.

Which is why I mentioned Japed in the beginning.

Eldritch is no different from any other Dick novel in this respect. Nor is it all that different dealing with the subject matter so dear to Dick's heart: the nature of reality, experience and religion. But the deftness and brilliance of the vision!

Dick takes things apart and lets you see what's inside. Sometimes he uses a scalpel. Sometimes an axe. But these are entrails he's examining. It's not for the squeamish.

I was worried when I read it. Eldritch had a big impact on me. Certainly on my writing. Dick also looks at human institutions with the full understanding they (and we) are absurd, with great affection for them (and us) and a little regret we can't do better. That point of view has stuck with me ever since.

I was happy to find that my worries were groundless. It's a sixties novel and that means some internal editing as it's being read. But it stands up as well as it ever did.

Sunday, September 15, 2013

Moving Up, Moving Out

(Picture from here.)

Remember Voyager 1? Tiny probe barely the size of a Geo Metro who gave us pictures of Jupiter and Saturn like we'd never seen them before? Brief acting career in Star Trek I but the less said about that the better.

Well, the little guy has all grown up and moved out.

That's right Voyager I has exited the solar system. (NASA announcement here.) I know he flirted with moving out before, hanging out in the heliopause for months. But this summer he finally cut the cord and went out to see the big wide world.

Voyager was launched by NASA in 1977. Usually, I like to talk about manned exploration of space-- which fits with my general biological point of view. Manned missions are like biology exploring the rest of the universe.

But I have to say NASA's unmanned missions have actually done far more than the manned missions have. I mean it's great we reached the moon and have the ISS. But manned missions, to me, are about space colonization and getting people off the planet. Exploration is a nice but secondary part of the goal. It's a perk.

The unmanned missions are about raw exploration and scientific data. And NASA has done a lot more of them than they ever put people into space. (Here's a NASA list. Here's a much larger list.)

NASA started with Explorer (There were 90 Explorer missions) in 1958 and now it's just a little more than fifty years later and we have a mission that has actually left the solar system. That's about two and a half human generations.

We like to make fun of the old SF books that had people colonizing the moon in the 20th century. Heinlein had Luna City founded sometime in the nineties. (See chart here.) Nobody had a good grasp on how godawful expensive space would be or how really far the planets were-- much less how far the nearest stars were.

It's interesting that unmanned exploration wasn't much talked about in SF. I mean there are some stories about it. Certainly, James Cambias has written more than one suggesting that robots are the way to handle space. Meat is just too fragile.

Meanwhile, in 1958 (coincidentally, the publication date of Heinlein's Have Space Suit--Will Travel) we started populating nearby space with machines. These days we have better than two thousand satellites in orbit. Most of those either are studying earth, handling earth commercial needs or are military.

But it wasn't long before we started looking outward. I'm guessing the first serious off-earth probes were the Pioneer missions. The first Pioneers launched for the moon. Some got there. Some didn't. In fact, from P-0 to P4 (which included 10 probes, all of which aimed at the moon) most failed pretty spectacularly. Of them, only one (Pioneer 5, launched in 1960) aimed for Venus. Later Pioneer missions, starting in 1965, looked all over the place. Pioneer 10 (launched 1972) reached Jupiter. Pioneer 11 (launched 1973) reached Jupiter and Saturn. The year after Voyager I was launched, the Pioneer Venus Project had its first launch with the Pioneer Venus Orbiter-- which continued to give us data until 1992.

Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 are on their way to escaping the Solar System, slowly following where their younger brother has gone before.

In parallel with Pioneer were the Ranger missions. Ranger was all about the moon and, like Pioneer, failed a lot in the early years. Ranger 7 made it in 1964 and we had our first close images of another planet. To give a comparison to the manned program, Alan Shepard launched in 1961 and by 1963 the Mercury program had ended with six successful missions and four missions that involved actual orbits. Man returned to space in later in the Gemini program by 1965.

The Mariner program ran in parallel with both Pioneer and Ranger. It began in 1961 and sent probes to Mars, Venus and Mercury. Again: initial problems with Mariner 1 and Mariner 2, both intended for Venus. Mariner didn't show success until Mariner 5, launched for Venus in 1967. Mariner 6 and 7 made Mars. Mariner 9 orbited Mars, sending back data for a year.

Then, there's Surveyor: those wonderful tiny probes that we actually dropped on the moon. Seven were launched. Five succeeded. One (Surveyor 6) actually managed lift off for several seconds and moved around a bit.

In 1974, just three years before Voyager was launched, the first Helio probe was launched to study Mother Sun. They sent data back to us for ten years.

Viking 1 touched down on Mars in 1976, one year before the Voyager I launch.

And these were just the NASA missions. There's the Russian Venera and lunar exploration programs. Not to mention the many, many Earth observatory satellites, some neither Russian nor American. Not all exploration need be done by a visit.

Then came Voyager I, the first probe to execute a Grand Tour of the Solar System. Voyager I let us see Jupiter and Saturn, so close and personal we could watch volcanic eruptions on Io and see the atmosphere of Titan. Later, the Grand Tour would be continued by Voyager II.

I don't know about any of the rest of you, but those first pictures of first the Jupiter approach and then-- oh, my!-- those pictures of Saturn are as strong in my mind as Neil Armstrong's first steps. This is the sort of thing we should be doing all the time!

Since then humans have had tremendous success exploring the solar system and elsewhere by probes and observatories. I won't dwell on them here-- this is about Voyager I.

In 1980, Voyager I performed a close flyby of Titan, spun around it with a gravity assist and left the Grand Tour towards interstellar space. In 1990, V-I gave us a Valentine's Day present of the Family Portrait, a mosaic of the Sun, Earth, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

The recent years have been one of getting closer and closer to the boundary of interstellar space-- the edge of the Heliosphere. In 2004 it passed the termination shock-- the boundary where the interstellar medium slows the outgoing solar wind to the point where compression begins to occur. At some point, it passed the termination shock and entered the Heliosheath, the area between the termination shock and actual interstellar space. In 2010, it reached the region of the Heliosheath where the speed of the solar wind dropped to zero. In 2011, Voyager entered a previously unknown area called the stagnation region or "cosmic purgatory," an area of particle turbulence where the wind actually curls inward back towards the sun. The dominant force here is interstellar particles and fields but the magnetic field of the sun is putting up a good fight.

Then, in 2012, it was thought Voyager I had exited the solar system. But in December it was decided it was a new region at the edge.

Then, 9/12/2013, NASA confirmed Voyager I had at last left the solar system.

Voyager I is getting old and cranky. Three different subsystems have had to be turned off in the last few years to conserve power. Two years from now the recording system will be shut down. Sometime in 2016 gyroscopic operations will be halted. Then, in 2020, the science instruments will be terminated one by one until sometime between 2025 and 2030, nothing will be working any more and it will go forward, cold and dark, on its way to Gliese 445.

It should get within a couple of light years in 40,000 years. And it left us with this cool, creepy sound.

Sunday, September 8, 2013

Schrodinger's Biology

I had a blog entry to enter in last week involving the 50 year anniversary of the Dr. Martin Luther King's "I have a dream" speech.

But I couldn't get it right. Sigh. I'll get it one of these days. Moving on.

One of the hardest concepts to grasp in evolution is its parallelism and interactivity. A mutation in one organism doesn't necessarily just affect the organism itself. It can affect its neighbors, predators, prey and its descendants.

A good example is feathers.

Last year the a team of Canadian, Japanese and American paleontologists announced the discovery of feathers on a newly discovered Ornithomimus specimen. (See here.) The discovery pushed the appearance of feathers back quite a ways, long before the birds appeared and certainly long before the feathers were used in any sort of flight. O. edmontonicus was flightless and weighed about 350 pounds. It had no flying ancestors to speak of. Consequently, the evolution of feathers had to have pre-dated flight and been used for other purposes. Two proposed uses for feathers are thermoregulation and social displays.

That is for the organism itself. Anybody who works with birds knows a few other uses. Birds use feathers to protect themselves from the elements-- especially aquatic birds. They use them for brooding eggs. In addition, birds have lice that love the protection and insulation of feathers.

Feathers affect predation by changing the physical appearance of an animal-- a feathered animal can appear much larger and more massive than it is. Predators have to adapt to the tactile difference between feathers, skin and (for mammals) fur. If feathers evolved in conjunction with warm-bloodedness, the resulting organism scales differently in terms of size, both in maximum and minimum sizes. In speed as well. All of which need to be adapted to by predators or exploited by prey. Nothing happens in a vacuum. This branch of biology is called evolutionary ecology.

If you consider a population of animals, each of which is given a unique combination of genes and developmental environment, each plays out a single thread of possibilities also unique to that organism. The possibilities are played out in real time and result in a statistical result: differential reproductive success for a given subset of the original population.

This is essentially a computational problem. If you take a set of different starting conditions and apply a computational algorithm to each of them, some will have a better solution set at the end than others. This is the basis for evolutionary computation, a subfield of computational intelligence.

Evolutionary computation operates by continuously optimizing the result using Darwinian selection methods. An evolutionary algorithm uses computational equivalents to reproduction, mutation, recombination and selection. "Fitness" is determined by how close the outcome maps to solution rules. Each "generation" is tested and those members that best fit to the outcome are selected for the next.

This can work both ways. Certainly there are algorithms that can be derived from evolution we might find useful. But can we view evolution itself as a computational process?

"Evolution" is an emergent property that derives from the lives of individual organisms-- how they cooperate, compete, eat and be eaten. We only see the process of evolution as it plays out over time. Each organism plays out the problem if its own survival. Evolution only emerges as a function of the reproduction of those individuals.

There is such a thing as DNA computing. This is using the chemistry of DNA to solve computational problems. Caltech researchers have managed to use DNA in implementing a circuit that can solve square roots up to fifteen. This article talks about multicellular computation networks. This article talks about proteins as computational units within the cell. And this one talks about computation using biochemical reactions.

Lee Segel has written this on computing a slime mold. He modeled it as a set of small automata that obey (relatively) simple rules. This looks to me as a step in the right direction. If a model of an organism is composed of computational units, can model of the organism be considered a computational unit? And, by extension, can the organism itself be considered computational. That would make evolution an emergent computational property.

So what is computation, anyway? And why would this be important?

Computation is the process of following an algorithm and obtaining a result-- transcription of DNA and copying your homework are both acts of computation in the most general sense. Computation is a physical process. That is, it is the product of physics and happens in the physical world. (A good article on the physical limits of computation is here.) Computational machines we normally use are made of silicon and use electrons. My favorite computational machine is between my ears is made of neurons and functions largely on Twinkies. (Also called a wetware computer or, sometimes, a brain.)

One type of computational entity is an automaton, an abstract machine. These are mathematical objects that can solve computational problems. One kind is a finite state machine, where a given machine is always in one of a finite set of possible internal states. A vending machine is a good example. It might be in a product delivery state, a money accepting state and a product selection state. You put your money in, you select the product, the product is then delivered. This machine cannot be in more than one state and the capabilities of a given state are specific to that state.

There's been a fair amount of research applying automata theory to biology. (See here and here.) How, then, to apply it to evolution?

The problem is that evolution and biology are complex statistical systems: a single solution, or even a single set of solutions, is not the goal. In addition any but the most trivial of biological systems are massively parallel. There's even a branch of biology for this: complex systems biology. There have been a number of interesting outcomes from this area. Wojciech Borkowski has proposed using cellular automata for the purpose of modeling macroevolution-- the macro processes that must be emergent and don't derive simply from genes and individual populations. There has even been some talk about another branch of automata theory, infinite automata theory, being applied to biology. (See here.) While the possible states of a biological system are very, very large, they are probably finite. But they may be large enough that they can be modeled as an infinite autumata.

But I got to thinking. Hm. A computational entity that is incredibly complex, massively parallel and whose outcome is always statistical. That sounds familiar...

Oh, yeah. It's a quantum computer.

And, when I looked, sure enough the late I. C. Baianu was looking into quantum automata (and here) and evolution. (See here.)

Now, I am not saying biological systems are Bose-Einstein condensates or entangled. I am saying there are enough similarities between how the systems behave that the math from one might actually apply to the other. I think Baianu was onto something.

Quantum computers represent a problem as all possible states in such a way that when the measurement event occurs a set of possible answers to the problem (with some probability of correctness) emerges.

Evolution is like that, too. Wherever a niche opens up a population of organisms try to take advantage of it-- consider it the initial problem state-- all trying their own unique approach. Approaches blend, compete and cooperate. At a later time, each path has reached a point of observation.

The difference is that while a quantum computer might function nearly instantaneously, evolution's solution is splayed out over millions of years.

Think of it as "real" time.

But I couldn't get it right. Sigh. I'll get it one of these days. Moving on.

One of the hardest concepts to grasp in evolution is its parallelism and interactivity. A mutation in one organism doesn't necessarily just affect the organism itself. It can affect its neighbors, predators, prey and its descendants.

A good example is feathers.

Last year the a team of Canadian, Japanese and American paleontologists announced the discovery of feathers on a newly discovered Ornithomimus specimen. (See here.) The discovery pushed the appearance of feathers back quite a ways, long before the birds appeared and certainly long before the feathers were used in any sort of flight. O. edmontonicus was flightless and weighed about 350 pounds. It had no flying ancestors to speak of. Consequently, the evolution of feathers had to have pre-dated flight and been used for other purposes. Two proposed uses for feathers are thermoregulation and social displays.

That is for the organism itself. Anybody who works with birds knows a few other uses. Birds use feathers to protect themselves from the elements-- especially aquatic birds. They use them for brooding eggs. In addition, birds have lice that love the protection and insulation of feathers.

Feathers affect predation by changing the physical appearance of an animal-- a feathered animal can appear much larger and more massive than it is. Predators have to adapt to the tactile difference between feathers, skin and (for mammals) fur. If feathers evolved in conjunction with warm-bloodedness, the resulting organism scales differently in terms of size, both in maximum and minimum sizes. In speed as well. All of which need to be adapted to by predators or exploited by prey. Nothing happens in a vacuum. This branch of biology is called evolutionary ecology.

If you consider a population of animals, each of which is given a unique combination of genes and developmental environment, each plays out a single thread of possibilities also unique to that organism. The possibilities are played out in real time and result in a statistical result: differential reproductive success for a given subset of the original population.

This is essentially a computational problem. If you take a set of different starting conditions and apply a computational algorithm to each of them, some will have a better solution set at the end than others. This is the basis for evolutionary computation, a subfield of computational intelligence.

Evolutionary computation operates by continuously optimizing the result using Darwinian selection methods. An evolutionary algorithm uses computational equivalents to reproduction, mutation, recombination and selection. "Fitness" is determined by how close the outcome maps to solution rules. Each "generation" is tested and those members that best fit to the outcome are selected for the next.

This can work both ways. Certainly there are algorithms that can be derived from evolution we might find useful. But can we view evolution itself as a computational process?

"Evolution" is an emergent property that derives from the lives of individual organisms-- how they cooperate, compete, eat and be eaten. We only see the process of evolution as it plays out over time. Each organism plays out the problem if its own survival. Evolution only emerges as a function of the reproduction of those individuals.

There is such a thing as DNA computing. This is using the chemistry of DNA to solve computational problems. Caltech researchers have managed to use DNA in implementing a circuit that can solve square roots up to fifteen. This article talks about multicellular computation networks. This article talks about proteins as computational units within the cell. And this one talks about computation using biochemical reactions.

Lee Segel has written this on computing a slime mold. He modeled it as a set of small automata that obey (relatively) simple rules. This looks to me as a step in the right direction. If a model of an organism is composed of computational units, can model of the organism be considered a computational unit? And, by extension, can the organism itself be considered computational. That would make evolution an emergent computational property.

So what is computation, anyway? And why would this be important?

Computation is the process of following an algorithm and obtaining a result-- transcription of DNA and copying your homework are both acts of computation in the most general sense. Computation is a physical process. That is, it is the product of physics and happens in the physical world. (A good article on the physical limits of computation is here.) Computational machines we normally use are made of silicon and use electrons. My favorite computational machine is between my ears is made of neurons and functions largely on Twinkies. (Also called a wetware computer or, sometimes, a brain.)

One type of computational entity is an automaton, an abstract machine. These are mathematical objects that can solve computational problems. One kind is a finite state machine, where a given machine is always in one of a finite set of possible internal states. A vending machine is a good example. It might be in a product delivery state, a money accepting state and a product selection state. You put your money in, you select the product, the product is then delivered. This machine cannot be in more than one state and the capabilities of a given state are specific to that state.

There's been a fair amount of research applying automata theory to biology. (See here and here.) How, then, to apply it to evolution?

The problem is that evolution and biology are complex statistical systems: a single solution, or even a single set of solutions, is not the goal. In addition any but the most trivial of biological systems are massively parallel. There's even a branch of biology for this: complex systems biology. There have been a number of interesting outcomes from this area. Wojciech Borkowski has proposed using cellular automata for the purpose of modeling macroevolution-- the macro processes that must be emergent and don't derive simply from genes and individual populations. There has even been some talk about another branch of automata theory, infinite automata theory, being applied to biology. (See here.) While the possible states of a biological system are very, very large, they are probably finite. But they may be large enough that they can be modeled as an infinite autumata.

But I got to thinking. Hm. A computational entity that is incredibly complex, massively parallel and whose outcome is always statistical. That sounds familiar...

Oh, yeah. It's a quantum computer.

And, when I looked, sure enough the late I. C. Baianu was looking into quantum automata (and here) and evolution. (See here.)

Now, I am not saying biological systems are Bose-Einstein condensates or entangled. I am saying there are enough similarities between how the systems behave that the math from one might actually apply to the other. I think Baianu was onto something.

Quantum computers represent a problem as all possible states in such a way that when the measurement event occurs a set of possible answers to the problem (with some probability of correctness) emerges.

Evolution is like that, too. Wherever a niche opens up a population of organisms try to take advantage of it-- consider it the initial problem state-- all trying their own unique approach. Approaches blend, compete and cooperate. At a later time, each path has reached a point of observation.

The difference is that while a quantum computer might function nearly instantaneously, evolution's solution is splayed out over millions of years.

Think of it as "real" time.

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Ergaster's Childern

(Picture from here.)

When I first moved up here to Massachusetts I did what I always do, I went to the science museum. There was an exhibit of the cave paintings. The docent talked about them and said (as close as I remember): "Who were these wonderful artists? It certainly wasn't these folks. They just weren't capable." With that he brandished a Neanderthal skull.

That ticked me off. First, because the cave paintings were made long after the Neanderthals had died out. So, while it's true they didn't do the work, since they were already dead it was a meaningless point. Second, it was a snide way at taking a whack at Neanderthals as brutes-- an odd sort of racism. Translated: "They weren't us so they couldn't have done this."

It's not an accident that my first published story, "A Capella", is about a Neanderthal cave artist.

Nothing sparks discussion like the Neanderthals. Were they brutes? Were they not so brutes? Clearly, we succeeded when they failed. How did we do that? Or, translated, in what way were we preternaturally superior to them? After all: we're here. They're not. We must be better.

There have been lots of hypotheses on the Neanderthal demise-- most of which involve some sort of compare/contrast relationship with competing humans. They had bigger brains than ours so that had to be addressed-- and it has, a few times. One study suggests that their brain organization is substantially different than ours. Neanderthals have a larger visual system than that of modern humans and that reduced the available space for cognitive systems. Another one implicated bunnies in their demise-- or, rather, their inability to catch them. Modern humans will eat anything: bunnies, squirrels, birds, each other. The Bunny Hypothesis suggests that Neanderthals did not have the capacity to be this flexible.

As time has gone on the differences in capability between Neanderthals and modern humans has diminished.

Do Neanderthals have complex tools? Check. There's one tool-- a lissoir-- was invented by Neanderthals before the tool was used by modern humans. In fact, there's a distinct possibility that humans learned about the tool from Neanderthals. Did Neanderthals have art and culture? Check, check, check and check. Neanderthals buried their dead with ornamentation, wore jewelry and make up. Did Neanderthals eat things other than big mammals? (I.e., the Bunny Hypothesis.) Check. Neanderthals ate fish and birds, processed wood and hides and ate their vegetables. They may also have understood that some plants had medicinal values. (See here.) Now that's pretty sophisticated.

It's not clear that they ate or didn't eat bunnies. It's also not so clear from what I've read how much small game there was to eat or when modern humans learned to catch it. Paleo-Indians subsisted largely on now extinct mega-fauna: giant beaver, ox, mammoths, etc. Not much different from Neanderthals.

A good deal of new information has been showing up since the Neanderthal genome was fully sequenced. Interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans has become pretty definitive now-- to the point a hybrid may have been found. (See here.)

A problem with understanding Neanderthals comes from mis-connecting our own tribe with Neanderthals. For one reason or another, Neanderthals have become defined by their opposition to human beings. There are differences between Neanderthals and modern humans. Possibly the ocular system as mentioned above. The olfactory neurological system in modern humans is 12% greater in size than in Neanderthals. (Which, of course, could not reflect any cognitive deficit comparing modern humans to Neanderthals. Right? Right?)

To me, the most interesting news that is coming out regarding Neanderthals is that they may have largely died out long before they met humans. There was little or no competition between the two groups, though there was enough encounters for interbreeding.

New radio carbon dating techniques (see here) make the time overlap between modern humans and Neanderthals problematic. This is interestingly corroborated with some DNA evidence (see here and here) suggesting that Neanderthal populations may have crashed prior to modern humans came to Europe. In fact, it may have been the sheer dumb luck of timing that a population of modern humans didn't buy the farm right alongside Neanderthals.

There's this concept of refugia in ecology. A refugia is a place of relative calmness when everything else is crashing down-- usually because of either local or global climate change. When the femets hit the windmill a hundred thousand years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum, modern humans hadn't moved north. Their refugia were safer than those of Neanderthals so much farther north. (See here and here.)

Neither group could protect the future. Things were going downhill-- I suspect both groups knew it. They both went where it looked like things could remain if not okay, at least survivable. But the range of choices between the two groups was different. Neanderthals got nailed. Modern humans fared better. When modern humans finally did get to Eurasia the remaining Neanderthal and Denisovan groups were tiny.

As they say, it's better to be lucky than smart.

Which brings us to the question of how did humans really evolve? Annalee Newitz suggests its a crooked, branching road that brought us to now, filled with little groups (such as the hobbits) that didn't quite make it to modern times.

There may even be a new addition to our ranks, the Red Deer People of southwest China. The find there dates to between 14,500 to 11,500 years ago and the skeletons show an intriguing mix of modern and primitive human qualities. Too soon to tell anything about them. But they did clearly overlap humans in time. Were they a relic population of humans? Were they a different sub-species, as were Denisovans or Neanderthals? Were they a completely different species such as Homo floresiensis? We don't know yet.