(Picture from here.)

We continually overestimate and underestimate ourselves. Our lack of ability to objectively evaluate ourselves is a source of serious problems for us as we try to navigate a future for which our evolutionary history has ill prepared us.

We are fully capable of considering ourselves the pinnacle of creation and lord of the world at the same time regarding ourselves as lower than any other animal. I've heard this in conversation. You probably have, too.

We are magnificent animals, emphasis on both words.

One of the terrific things about scientific thought is we can take its aperture and apply it against anything. We are only limited by-- well, our own limitations as stated above. The granular representation of ourselves to ourselves.

There was a terrific cartoon I saw in the seventies that I've not been able to trace down. The image is of a bunch of animals-- human, dog, giraffe, hedgehog, chimp, cow-- and they are all thinking, "And God made

So, when we point the aperture of science at human beings we have to leave our own self-involvement at home.

We think of the future all the time and we build things. We are our own best metaphor for the rest of the universe. So when we think of evolution and apply ourselves to it, it's hard not to have a designer around. After all, a watch isn't much different then a flower, right? If you see a watch on the ground, somebody must have built it. Therefore, if you see a flower on the ground...

Of course, it doesn't work that way. Not even for watches.

If one had no knowledge of watches, it's not even clear we'd recognize it as a watch-- after all, the antikythera mechanism was built by humans but we didn't know what it did for years. But let's presume we can recognize it as built by something.

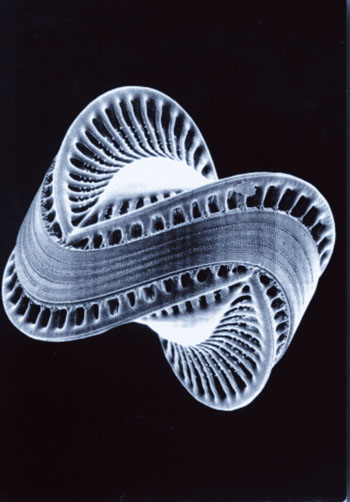

(Picture from here.)

Could it be like a diatom? Few things are more beautiful and complex than the cell walls built by these one celled algae.

Okay, let's say I spot you the watch was made by a thinking being and we might even know what it was. But even then it would be a creature that has the concept of time and number, used some sort of grasping appendage of particular dimensions and possessed perception of such a resolution that would make such a watch useful.

Pretty soon you either end up with a really odd watchmaker or evolution.

The history of science, along with everything else, is littered with the shards of people's hypotheses that were grounded not in good thinking but people's self-conceptions. Evolution is no different.

One idea that people have is the concept of progressive evolution. Yes, if the life of the universe were metaphorically represented as a calendar year, we would have come to light in the last five minutes. But that only means that it took that long to develop an entity as enormous of faculty as ourselves. Right?

Well, not quite.

Now there is progressive evolution but not in the way most people mean. Evolution is always about local adaptation to local conditions, whether those conditions are external to the species or are expressed within the species. But each species exposes its heritage to the selective pressure of the moment.

If we look at the evolution of the horse, for example, we start with eohippus, a tiny dog sized forest dwelling herbivore, and end up with Seabiscuit. However, that starting point was from the very beginning a herbivore, a hind gut fermenter with tiny hooves instead of claws on the edge of its pads. It had starting material. Evolutionary descendants of modern horses would encapsulate all of the evolutionary changes that happened since eohippus. They wouldn't be starting with eohippus.

Similarly, humans forebears started walking upright. The selection here was on the feet long bones of the legs and the hips. Look at that foot: big toe, toes in the same plane. Turns out the developmental mechanism that makes feet is closely associated with the developmental mechanism that makes hands. Big toes drove human thumbs. (See here.)

Wait, you say. Monkeys have hands that they use... as hands. Humans and monkeys derived from the same stock. That suggests that hands predate human beings walking upright. So there!

Yes! Absolutely. Brain studies of how the hand is controlled the brain suggests that all of the primates use similar mechanisms and, in fact, there is generally more CPU power dedicated to the hand than the foot.

So, our ancient ancestor got hands and feet as part of the primate package. He got brain organization to use them to make tools-- we know our cousins use tools as a matter of course. We have to presume that our ancient ancestors did, too. Then, as we moved toward upright posture, that modified our feet, giving a little push on how hands were made. That exposed thumbs to selection. Which allowed tool using to become a greater selection trait. Which started to drive hand selection.

Meanwhile, this brain behind the hands-- already pre-disposed to make tools-- also gets selected for.

And we're off to the races where we can send men to the moon but can't (or more honestly, won't) keep everybody fed.

Magnificent. Animals.

I admit I'm pretty much a materialist. By that I mean that I don't have any emotional attachment to any non-physical world. Whatever makes us human lives in our brain and our bodies.

That said, if we are the sum of all of the evolutionary decisions made before us, somebody-- in fact, a lot of somebodies-- made decisions that culminated in altruism, beauty, music, commerce, husbandry and a whole slew of other things that we do either uniquely or incredibly better than everything else. To the point where we take the very guts of living things, their reproductive and physiological components, and repurpose them to to our will.

No one can take that away from us and no one should even try. To paraphrase Olivander from HarryPotter, we have done great things. Terrible things but great.

The same species that wages war, creates hospitals. That practices genocide, feeds the poor. Yes, we are red in tooth and claw but we are gentle and kind as well.

It's time for us to accept who we are and what we can do. Not as the pinnacle of creation but as the most powerful vertebrate on the planet.

The first step, I think, is to see ourselves clearly.