(Picture from here.)

I don’t usually talk here about shenanigans on the public stage. But today, I’m going to make an exception.

I had a troubling phone conversation with a friend the other night. We’ll call her Brenda and her spouse equivalent Brian, for purposes of this discussion.

Brenda was telling me how Brian was ready to jump in his car and drive to help in the January 6th insurrection. She wasn’t having any of that and kept him home.

Brian got all of his news from social media—specific social media sites, at that. Social media sites that have been shown to lie. But Brian’s mind was fixed. He was convinced of the truth of these sites. Other data sources that showed they were lying were merely revealing themselves to be liars, themselves.

There’s a diabolical beauty to this sort of thinking: a standard is set up that cannot be challenged and, therefore, anything challenging that standard must be, by definition, in error.

This changes the field of discussion from rational thought to religion. To be clear, I am not against religion. But here the cognitive mechanism that makes some religions work—accepting scripture as revealed truth of one sort or another—is being used for other means.

Once that transition is made, no further intellectual discussion is possible. The conversation has moved from the cerebral to the emotional. Emotional discussions can only be fruitful when emotions are directly engaged, not in a faux scholarly way. If people argue out of fear, then that fear must be addressed. What they are arguing about is irrelevant. It’s the fear that is important. This is true for other emotions as well.

To reuse what Heinlein said in Glory Road, “…facts do not sway them in the pursuit of a higher truth.”

This is a problem, though. Because we need to address facts. What can you do when what you want to happen is thwarted? The obvious answer—the one we teach our children—is you accept the setback and work around the problem or right the wrong. When we teach that, we always say, explicitly or implicitly, that this means working through proper paths. If you get an F on your report card, you don’t shoot your teacher in an act of vigilante justice.

I see this as a twofold issue.

The first part is determining what is fact. These days, that’s hard enough.

Social media is a primitive mechanism for determining fact. It’s the modern-day analog of village gossip and just as reliable. It’s primarily built to convey emotion, which it does quite well. The whole underlying desire to connect to one another is emotional. It’s not surprising, then it fails spectacularly at distributing facts.

In the last hundred years and fifty years or so, we’ve built an entire news industry to propagate news: facts written as story. It is an imperfect, clunky, stumbling mechanism, prone to tipping one way or another depending on the whim of the moment and without the self-correcting mechanism of scientific peer review. It’s like democracy: it’s only good when compared to all of the other mechanisms.

News, like anything else, has to be vetted. We all have different ways of doing so with various degrees of success. Personally, I have a set of test subjects where I think I know the correct answer. Usually, this involves aeronautics or biology or computing—something I’m professionally competent in or something I’ve invested a lot of research time in. If a news source gets those right, I figure it has a higher probability of getting things right about which I’m incompetent. I also give higher credence to those news sources that give their sources.

A number of years ago, I found a story on the Human Events website that seemed strange. So, I followed it from source to source only to find my way back to a set of stories that referenced each other. I never did find an original source. Possibly, the story was made up. Or the story had sources I could just never find. The fact that I couldn’t find the original source reduced my trust of the story, and the site.

But the second issue—the more important issue, as far as I’m concerned—is that we have to recognize our own incompetence and the incompetence of others. News stories have to be vetted against a standard. Most importantly, the news stories have to reflect actual facts. Facts, in this case, are verifiable circumstances that are independent of our point of view. If I’m inclined to view the Palestinians favorably, I cannot dump facts that count against them.

This is, to me, the main problem with social media and why it’s like village gossip. We pick sources that are inclined towards our point of view over our perception of fact.

Worse, we have the Dunning-Kruger effect to consider: people are incapable of determining their own level of competency at things they know little about. Social media denies the D-K effect. Its underlying presumption is that the selected crowd that is telling you what you want to hear is capable of telling you the truth. It might be a set of capable people but there’s no standard against which this can be judged. And it flies in the face of our own deeply held belief that we are as good at anything as anyone else.

Instead, we must face our own incompetency and create mechanisms to guard against it. I am not a political theorist. But, I tend to think that a political theorist that has the credentials of a Nobel Prize to be worth listening to. He has to be vetted as well. And, yes, it never ends. There will always be a level of uncertainty and one must learn to be comfortable with this.

Americans are particularly susceptible to this problem. Built into our psyche is the unfounded belief that anyone can do anything. “Anyone can grow up to be president,” as the saying goes. Implied in a modern interpretation of this idea is that anyone can do anything without effort. We can determine competence without research. We can determine moral truth without searching our hearts. We can determine right action merely by being present. Often, with a gun. Batman says it, so it must be true.

Moral nuance need not apply.

I don’t have a solution for this. Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, years ago: “You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts."

That notion seems to have disappeared.

I wish I had a solution for this. Better education. More money to schools. Bring back the FCC Fairness Doctrine. Legislate truth in news.

But I think none of those will work. There’s too much money these days in disguising opinion as truth—and revealed truth, at that.

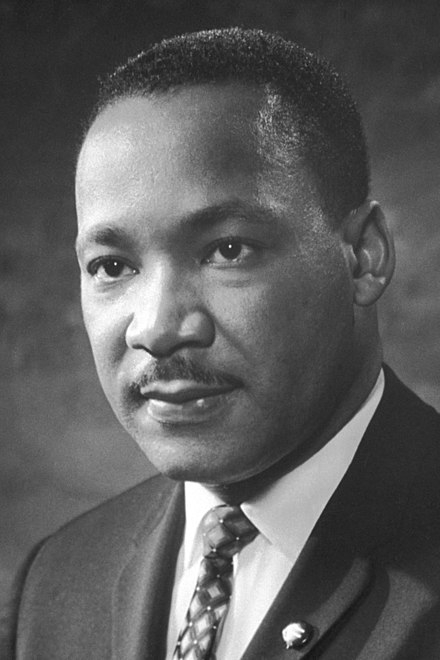

Possibly, the best we can do is what I once read attributed to Martin Luther King, Jr., but can now no longer find: “do good, eschew evil, and bear witness.”