(Picture from here.)

I hurt my hand this week.

It’s a long and sordid story involving using a winch to raise a 200+ pound wood lathe and then letting go at an inopportune moment. The crank whizzed around and caught me at the base of the thumb.

That’s the short version. The long version resembles the song Sick Note.

The result caused me a day or so where my right hand was essentially useless. Nothing makes a limb more important than the inability to use it and it got me to thinking: where did that hand come from?

Never one to miss an opportunity, I started trying to figure this out.

We are mammals.

Mammals got their start three hundred million years ago. But that’s not so critical to this discussion. What I’m interested in is what mammals were like back towards the end of the Cretaceous, the stem creatures that radiated out when the dinosaurs died out: the Cenozoic Era.

The first part of the Cenozoic is the Paleogene. During this period the primates and rodents first evolved. Anyone who’s ever seen a mouse must have noticed their tiny hands. Since primates also have hands, hands must have predated them both. Natural selection works on what it has. A trait that is common between two related groups is likely to have originated before they split. We have a primate hand with an opposable thumb. Rodents do not. But we are not the only mammal with such a thumb. So do opossums and koalas. Likely, they originated their own plan.

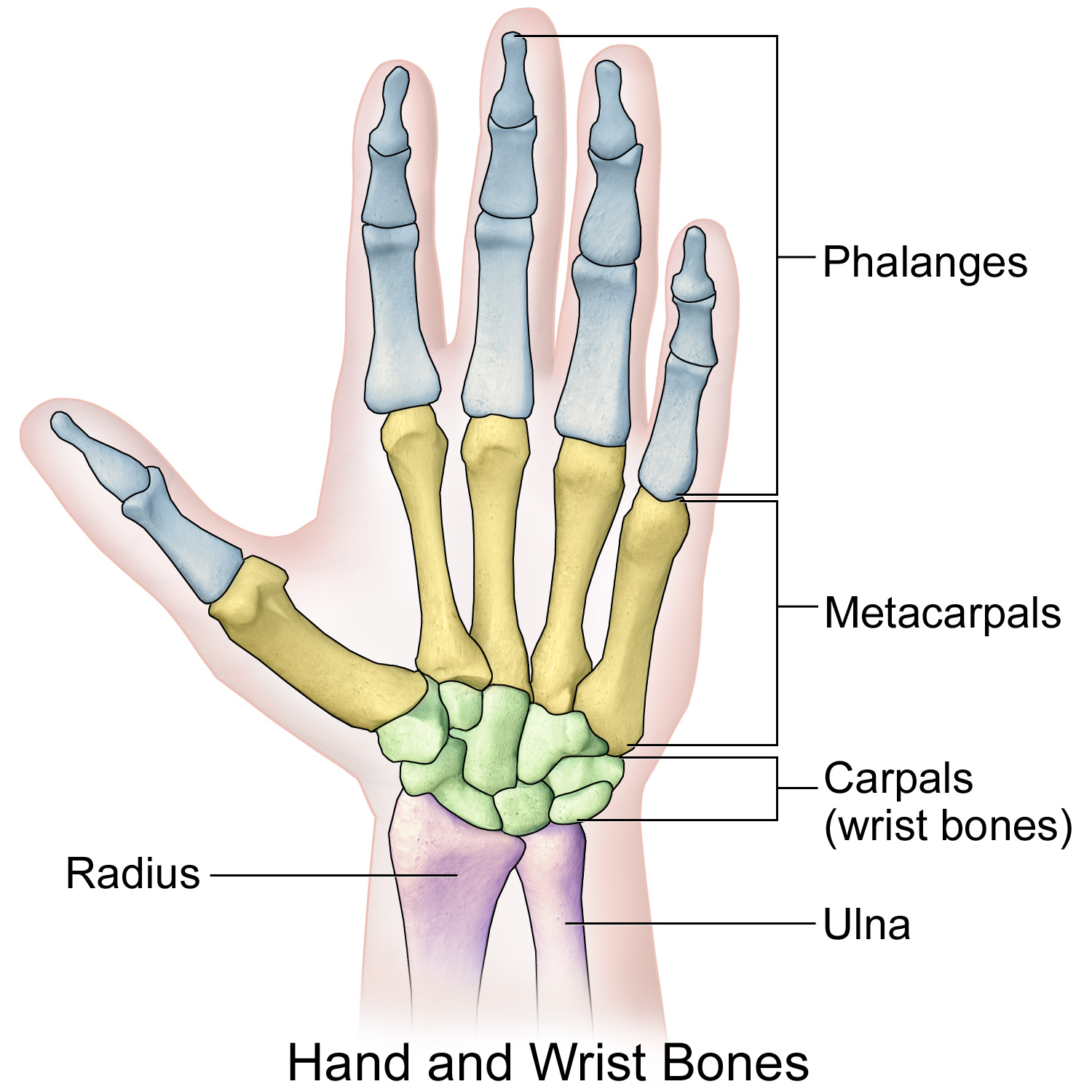

Regardless, prior to primates, there were tree shrew like creatures that had four fingers and a thumb. They inherited that from much more primitive ancestors. If you look at lizards or even amphibians, you see that same single upper arm, proceeding to two forearm bones, a cluster of wrist bones, followed by the finger bone pattern. The muscles of the forearm power those fingers. This is the pattern land dwelling tetrapods started with.

Primates inherited that and took to the trees.

Size matters. A mouse climbing up a tree doesn’t need a strong grasp. But a much heavier monkey does. Monkey hands are strong. Strong enough to swing from branch to branch. Strong enough to drop a story or two and catch themselves on a branch and keep swinging. I mean we’re not talking twisting phone books apart (heh. As if there were still phone books.) strong, but much, much stronger than a mouse. Here is a video of a gibbon swinging through the trees. Check it out starting about 1:11.

As I stated before, hands are powered by muscles in the forearm that reach tendons down into the fingers. There are some muscles in the palm of the hand surrounding the thumb but most finger strength resides uphill.

The Old World Monkeys and the New World Monkeys split when the new world was colonized by old world relatives., about forty million years ago. There’s a lot of discussion how this happened since the continents were already separated. A land bridge might have been involved. Or rafts. Regardless, the OWM were the ones that were left behind. The tailless apes, the Hominoidea separated out about 25 million years ago and the Hominidae, the Great Apes, split off from the Hominoidea about 14 million years ago.

By this time were talking some quite large apes, multiple tens of kilograms. Gorillas are commonly over a hundred kilograms.

The orangutans split off from the Hominidae leaving the Homininae: what would become gorillas, chimps, and humans. The gorillas split off, leaving the Hominini. The chimps split off and left is as the Hominina.

If anybody was concerned we weren’t self-involved enough, I submit the above Hom* sequence, all of which are human centric. When I was in graduate school, we had a continuous gripe about how human anatomy and non-human anatomy. Consider the anterior vena cava and the superior vena cava. Both drain the head end of the body. They are exactly the same structure but in one case the animal is standing up and in the other the animal is on all fours. My old anatomy professor said we should just visualize the human on its hands and knees. All animals can fit in that same box and we can use the same terms.

Anyway. By the time genus Homo comes around, the human hand is pretty much conserved. In fact, one of the interesting things about Lucy’s clan was not only that she was standing erect, her hands were pretty human, too.

So, now we know the heritage of the human hand, what changed for us?

There’s some evidence that human hands are more primitive than chimp hands and my have more in common with gorillas. Both gorillas and humans have pursued a terrestrial lifestyle while chimps are more arboreal. This means that our hands conserve more traits of the last common ancestor between humans and chimps. That said, observing the comparative photographs above, show significant differences between gorillas, chimps and humans. Human thumbs have more mobility than either gorillas or chimps. It’s easy for a human to touch the thumb to each finger easily and with some strength.

My suspicion, however, is the anatomical differences are deeper than the apparent musculature and bone. For one thing, our hands have been used alongside tools for nearly three million years. The use of tools has had an influence on the physical structure of our hands in some ways. More importantly, it has changed the way our brains use our hands. No other animal on earth uses tools as extensively as we do. This is a case of synergistic selection. We have a selection for better use of tools which requires a better brain. That better brain sees new uses for such tools, which then, selects for better brains to use those new tools. A virtuous positive feedback loop.

Which brings me back to my injury. Look at the human hand on the left. The winch crank struck the bone at the base of the thumb. Yet, the pain that made me think I’d broken something happened on the opposite side of the hand. Right where the carpals connect to the ulna.

It turns out there’s a cartilaginous pad in that little corner between the carpals and the ulna. It serves as a cushion when the hand is moved coplanar with the arm as opposed to when the hand rotates. The doc said this little pad is what was injured. That usually occurs when there is an abrupt and violent movement of the hand to compress that pad. Which must have happened when the winch crank struck the other side.

I’ve been unable to find the evolutionary history of that little pad but I suspect it goes back a long, long way.