(Picture from

here.)

We’re

now in our final harvest: chestnuts. Now, I’m in a fairly good position to

judge the entire season.

It wasn't good.

First,

let’s talk about the chestnuts.

We have three chestnut trees: Big Guy, Little Sister, and

Baby. Big Guy is an American chestnut, hybridized with a Chinese chestnut and

backcrossed to create an American chestnut with blight resistance. He’s fully

grown and has been producing nuts for several years now. Little Sister is a

modified Chinese chestnut that can cross fertilize with Big Guy so we get nuts.

Chinese chestnuts are naturally blight resistance. Baby is a mammoth American

chestnut of indeterminate blight resistance. She is only about four years old

and not really flowering yet. All attributions of gender are completely

arbitrary.

This

year we’ve harvested in excess of forty pounds of chestnuts from Big Guy and

Little Sister. Harvesting has to be done differently between the two trees. Big

Guy drops the burrs containing the nuts. Little Sister opens the burrs on the

tree and drops the nuts. We’re always in competition with the squirrels.

Forty

pounds of chestnuts sounds like more than it is. Chestnuts are made of three

components: burr, husk, and nut. The burr is spikey. The spines go through most

gloves. The husk then has to be removed. The remaining nut must then be dried.

The forty pounds is husked, undried nuts. So, it will be significantly less

yield when we’re done processing them.

Using

Big Guy as an example, a burr is supposed to hold up to three nuts. If there

isn’t sufficient pollination, there might be burr filled with “flatties”: nuts

that weren’t pollinated turn into this strange looking flat nut. Not even the

squirrels like it.

We got a

lot of flatties.

In

general, we had a problem with pollination. Mostly we blame the weather. We had

a warm May, cold and raining June, mixed rest of the summer. The chestnuts

flower and get pollinated in the May-June time frame. Consequently, we didn’t

get as much of a harvest as we would have liked.

But the

weather is even stranger.

We’ve

had a very warm September and October. It didn’t get much below sixty until

mid-month and we’ve had no frost or even any danger of frost. At one point, Big

Guy was sporting flowers on one branch while adjacent branches were making

burrs.

I’ve

mentioned before about the persimmon which set about a dozen fruit. Usually, we

get pounds and pounds of persimmons. Ditto Cornelian cherries. We had an

unusual infestation black rot on the Concord grapes and the Marechal Fochs had

a lot of immature grapes when we harvested them.

We’ve

been seeing this pattern for the last several years. And it’s only getting

worse. There’s a number of other indicators. Back in the day, we’d get some

warmth through May but didn’t dare plant the outside garden until Memorial Day.

By September, we’d be having cool, dry nights and certainly by mid-October,

we’d had a frost and be in brief warm spell in October. During the winter, we’d

get sticking snow starting sometime in December, a thaw in late January, then

socked in on snow and cold temperatures in February through early March. (Cold

means hovering in the low twenties with a drop below zero for a few days at a

time.) Then, things would be spotty all through May.

That is

not the case these days. The pattern seems to be evolving that we have an

elongated comparatively wet fall up until late December. Then, a snow/thaw

cycle punctuated with occasional plunges well below zero. March and April are

still quite changeable. Beginning in late April, the weather turns quite warm

through May, followed by a cold, wet June. Looking outside on 10/18, we have

the first true fall day. It was in the forties last night and today it is in

the sixties.

Just a

few years ago, we had Christmas dinner out on the picnic tables. It was too

warm to do it inside.

This is,

of course, a local manifestation of climate change.

We are

not subsistence farmers. We’re more advanced gardeners. But the issues that are

plaguing us are only larger agricultural problems as evidenced in our small

space. I have a friend of mine from Georgia who is gratified the weather is

more like what he’s used to—and gratified he’s no longer living in Georgia

which, I think, is moving away from habitability.

My point

is that climate change is messing with our food supply now. It will mess with

it more in the near future. We are going to have a collision in the close

generational future between climate change, crops that are not adapted to the

new climate reality, and nine billion people. This is fact now. This is

what is baked in from what we have already done. The future does not look good

for bananas, cocoa, and coffee. We are even entering the time of climate

induced sickness.

And we

are adding to the problem every year.

I can’t

say this enough. We are seeing this now. We will be seeing more. The CO2 we’ve

already added to the atmosphere will be there for thousands of years. The

methane will be there for hundreds. If we stopped right now, the CO2 would

cause the temperature to top out at +2

degrees Celsius. That’s what I mean by baked in. Every year we add

another gigaton or two and that becomes baked in. Every year after that.

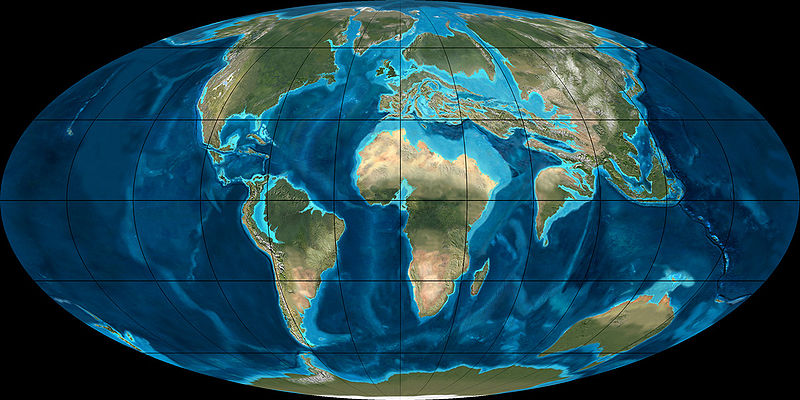

2C is a third

of the way towards the Paleocene-Eocene

Thermal Maximum (PETM). From what I’ve read, that world would be a

miserable place for us.

There

are people whose fortunes are committed to making this problem worse. At this

point, I tend to think that anyone who saying that climate change isn’t

happening is either uninformed or making

money off it. We should not be arguing whether or not to fix this. We

should be arguing how to fix

this. We should be starting those fixes now.

Kübler-Ross’ five steps of grief are denial, anger, bargaining, depression

and acceptance. I think it’s a good model for handling any catastrophic change

in life. I think it’s applicable to our handling of climate change.

I just wish the hell we’d get past step one.