People who don’t believe in evolution make me tired.

(Picture from here.)

For one reason, it’s like saying I don’t believe in the sun. The sun is there whether one believes in it or not—the existence of the sun is independent of belief. The fact of evolution also exists independent of belief. The obscuration of the sun by clouds or night does not change the fact of its existence.

One of the most tiring objections to evolution is the “statistically unlikely” argument. This is the idea that something as complex an organism as a human being—or whale, fruit fly, or starfish—could not arise by random chance. It’s too unlikely.

This is true and has nothing to do with evolution. There is very little randomness at work in evolution.

Certainly, the frequency and location of mutations are random since many of them result from random events such as cosmic rays and the like. However, it’s interesting that many organisms (I’m looking at you, tardigrades) have evolved mechanisms to resist radiation induced mutations. This reduces the effect of random mutations. If there are mechanisms to repair damaged DNA, their random effect is reduced.

The other random effect—random to the point of the organism—is the change in the environment. A fruit fly that has evolved on a volcanic island for a couple of million years is unprepared for the next eruption.

These arguments almost always involve animals—probably because even the most hardened anti-evolutionist can usually recognize that humans have kinship with animals. Plant arguments rarely come up. By which I infer that evolution is okay for plants, bacteria, and fungi but not allowed for animals. Go figure.

But animals have mechanisms at their disposal that can introduce variation and drastic changes without the messy need for mutation: sex and the evo-devo gene toolkit. We’ll talk about sex first. Everybody likes to talk about sex.

Sex is a brilliant mechanism for introducing variation within a species. It tends to preserve a diversity of features since each organism results from a combination of features from the parents. It actively stirs the pot of genes in the gametes that meet and create the next generation. These features can be selected for or against—or both. In Sickle Cell Disease, when a child inherits a specific mutation for hemoglobin from both parents, the hemoglobin forms abnormally and the red blood cells are unable to carry oxygen efficiently. A bad disease that we would expect selection to work against. However, when a child inherits a single copy of the gene, it appears to confers some protection against malaria. Thus, there are selective pressures in both directions.

Sex provides the mechanism for bringing up gene combinations and present them for selection. It’s important to remember that natural selection is not operating against genes. It’s operating against the reproductive success of an individual organism. The individual organism’s success might—or might not—be a result of the organism’s genes. For example, consider a herd of bison in Wyoming at the end of the last ice age. The ice is in place, limiting their reproduction in the area. The ice retreats, opening up new areas for grazing. The bison numbers increase. None of that is due to the genetic nature of the bison.

Consider, though, the same bison when the ice cools down the area. The bison with the longer hair and better fat distribution might have a longer reproductive life span and therefore spread their gene combinations throughout the herd. That is natural selection against the feature set of the organism.

The anti-evolutionists like to call changes like that microevolution. The don’t like what they call macroevolution, like the creation of eyes or wings. Generation of novel structures, like eyes, or unique adaptive characteristics, like giraffe necks, cannot be the same mechanism that just makes hair longer.

Interesting idea. You could redefine the terms into trait evolution—such as hair length, skin color, or tail length—versus structure evolution—such as eyes, bones, fingers.

There is some merit in this since changes in structure are fairly rigid in their degrees of freedom. An organism evolving a new feature—eye, ear, voice—must begin with something to start with and as the features change, there is no opportunity for the feature to function negatively. A structure on the way to an eye, for example, can’t have an intervening stage where the structure is maladaptive. Then, natural selection would work against it.

The evolution of structure is a tricky business.

Animals undergo a process of development from fertilized egg to reproductive maturity. Depending on the organism, there are differing numbers of stages and differing quality of changes. Egg to human is relatively straightforward even if extraordinary complex. Egg to butterfly involves a midpoint change where the soft larval organism turns into a gelatinous goo that reorganizes itself into a hard shelled adult. The whole process of egg progressing to larva progressing to adult is an dance orchestrated by genes.

That said, it’s important to know that there is no gene for a giraffe’s neck or a the elephant’s size or a the fish’s flipper. These are the emergent properties from the process of development.

Development is the process of expressing genes in sequence, with each cell responding to other cells in different ways and at different times, such that the result is a functioning organism. The toolkit genes control that sequence.

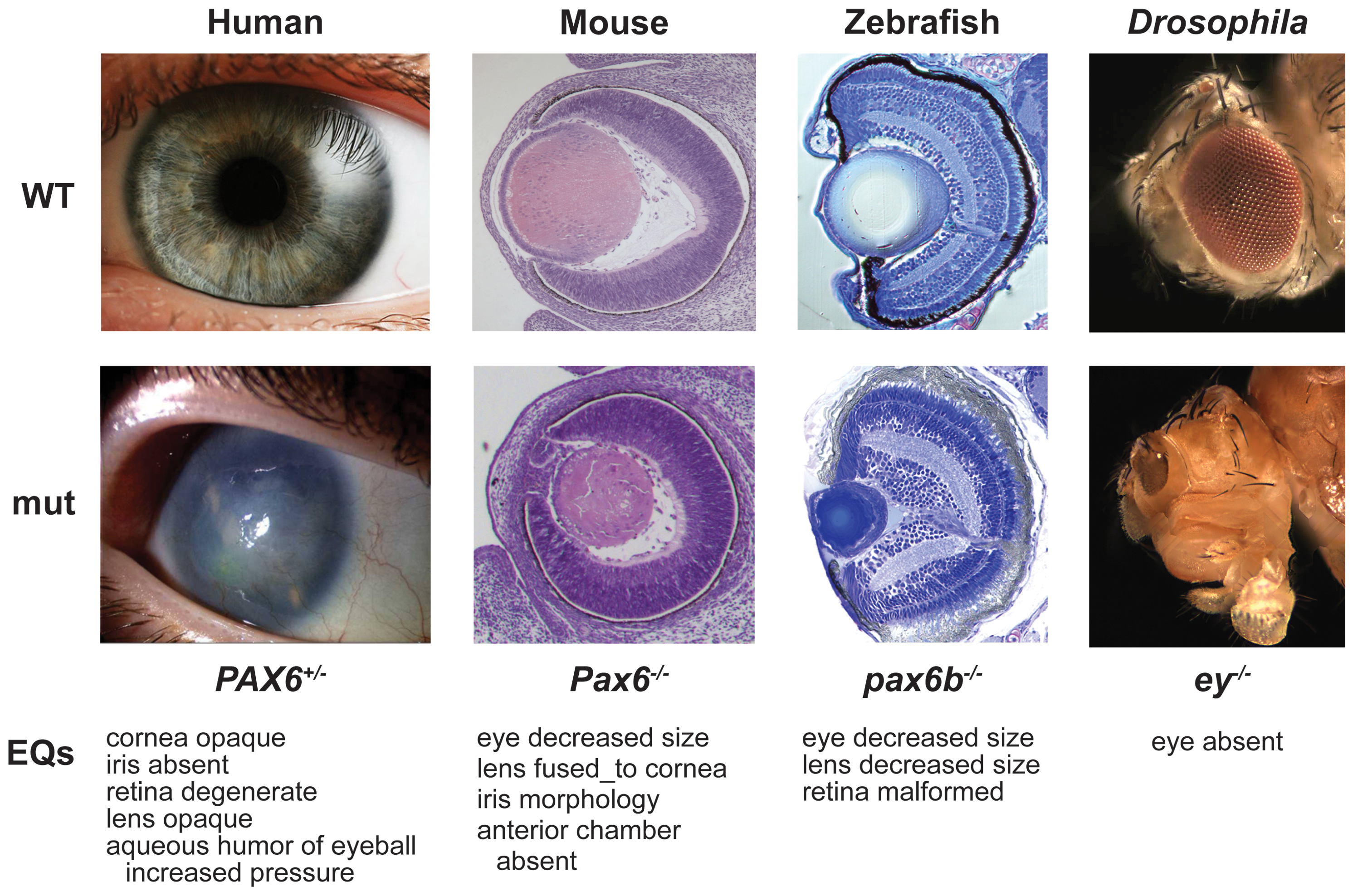

The toolkit genes are ancient and highly conserved across phyla. The genes responsible for eye creation are similar between insects, vertebrates, and cephalopods. The hox genes are responsible for body plan expression. The axis from head to tail, where limbs form, etc., are the province of the hox genes.

Many people have the idea that genes determine the organism and that is true. But along with this is idea that there is a single gene controlling a feature—a gene for height, intelligence, musical ability. Certainly, genes are involved in these things but not in a one to one fashion. There is no gene that gets turned on strongly to make Einstein and didn’t turn on so strongly to make me.

Development is more like improv under direction. The hox genes say make a limb here and a collection of genes are turned on that create growth centers that then propagate bone, blood vessels, and nerves. One gene might get expressed many different ways in many different places at many different times. Different combination of genes might cooperate one way and make a toe. The some of those genes cooperate with a different set of genes and make a kidney.

Think about it. Humans have been determined to have about 20,500 genes. There are far, far more than that many traits being expressed in a single human being. Therefore, there can’t be single genes for every trait. Certainly, there are some chemical compounds—like hemoglobin—that are so incredibly important that there are genes specifically dedicated to creating them. Genes are responsible for proteins and hemoglobin is a protein. Most traits—the shape of your nose, the olfactory acuity of the dog, the sense of balance of a cat—are the products of scores of genes acting together.

This presents the opportunity for the evolution of novel and complex structures. Again, all natural selection needs is diversity of features and differential reproductive success. Selection to create a large brain requires brain size and structure variation. Selection to create the lungs of birds requires variation in lung development. Selection to create the hollow bones of dinosaurs from which bird bones derived requires variation on bone development. All of these must derive from variations in structural development—changes in the evo-devo toolkit, where a slight change in timing or quantity can have far reaching consequences.

But I can hear the anti-evolutionist respond: “Well, the evo-devo toolkit is too complex to have evolved on its own.”

Really? At this point, finding a deep homology between humans, fruit flies, and round worms one might think: give it a rest.

It’s not about you. If something did create the toolkit back in the dawn of time long before the vertebrate lineage, it wasn’t interested in us.

No comments:

Post a Comment