If you read any book on fiction writing, you’ll end up reading about the three-act structure.

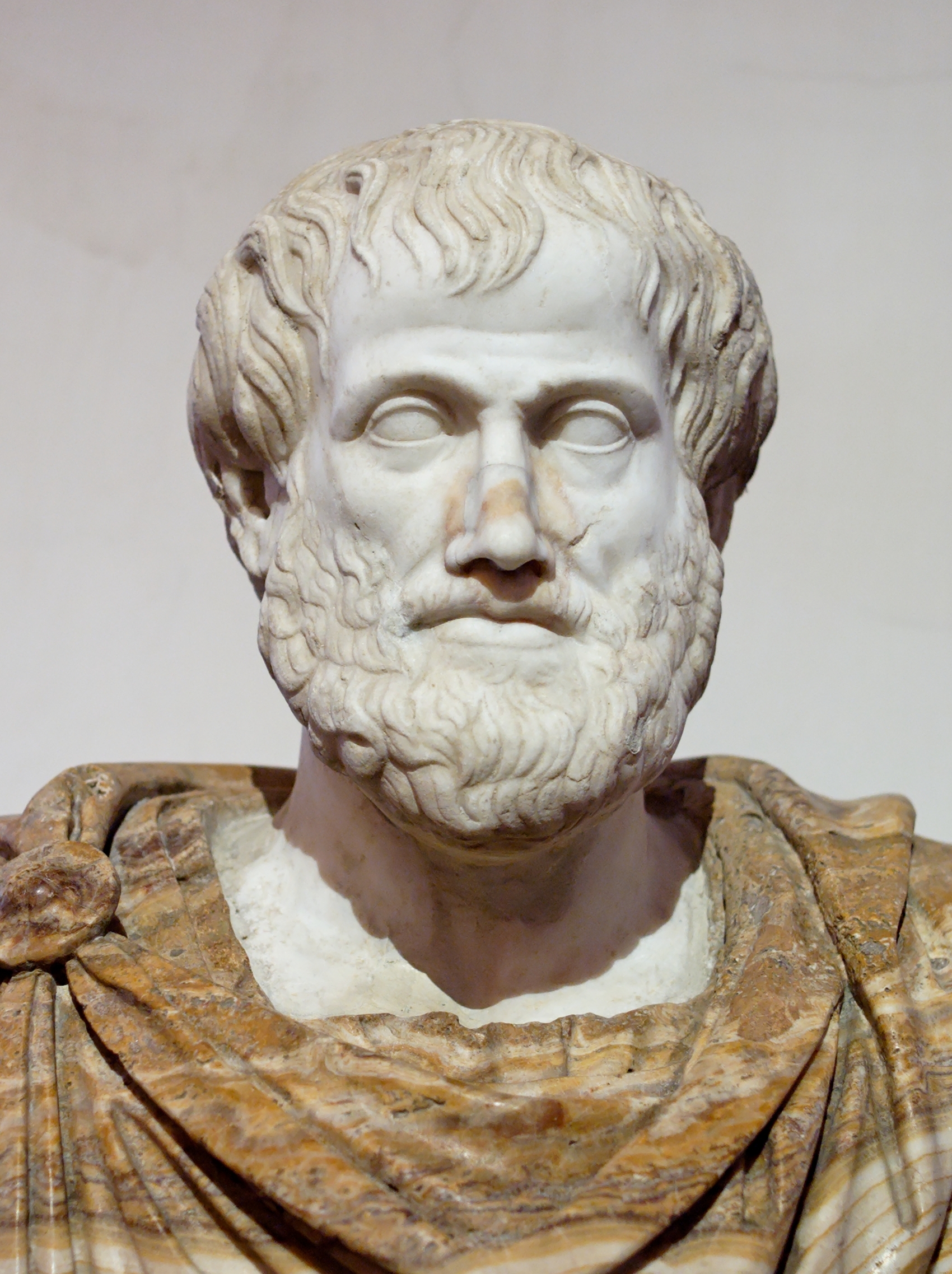

(Picture from here.)

Often, it is discussed as a character proceeding along a particular path that is then disturbed by some kind of inciting incident. The character then spends the rest of the story attempting to return to the character’s original path and failing. Ultimately, the character attains some kind of resolution that is not the original character’s arc but a new path and the story ends.

It is attributed to Aristotle but he observed its existence. He didn’t invent it. It is even likened to Newtonian mechanics: an object with a given direction and velocity will remain the same until perturbed by a collision and that will result in a new direction and velocity.

It pretty much describes every Hitchcock film ever.

This is one venerable and respected description of story plot and I won’t criticize it at this time but it leaves unknown the reasoning, understanding, and heritage that creates the character path in the first place.

Back in the eighties when I was first working in the software field, I met a very interesting individual. Let’s call him Dwayne.

Dwayne was very smart and a recovering alcoholic. He did not disguise either of these features. In his opinion, people who were put off by either of these qualities were not worth his time.

(He had an interesting take on alcoholism and people’s response to it. To paraphrase, if someone came out of anesthesia and acted bizarrely, people would blame the drug. Why, then, are people surprised when drunk people act out? It’s the drug, not the person. The problem is getting the drug out of the person’s system. But I digress.)

Dwayne viewed people as having a normal state. This is not “normal” in the sense of average or societal acceptance. Instead, he viewed it as the ground state of the person. The state where the person felt comfortable. Where things were accepted. Where things felt normal. And that people attempted to preserve that state and defended it regardless if the state were good, bad, or catastrophic. In his opinion, determining what one felt was normal and then critically standing it up against a desired state was the job of a thinking adult. Altering one’s perception of normal was how one created change in one’s self.

I left that job in the early eighties and lost contact with Dwayne. I suspect he never gave me much more thought but I’ve been thinking about him—and normalcy—ever since.

Normalcy determines the path the individual remains on in the absence of other perturbations, either internal or external. If one grows up in an alcoholic household or as a child soldier, that feels normal. It’s not good. It’s not even necessarily what the individual wants. But it is what the individual knows and that gives it a strange kind of comfort. A good story is standing up an example that conflicts with that normal, either worse or better, and having the character wrestle with attempting to reconcile a familiar ground state with the possibility of something new.

The advantage of this approach to characters is that it opens a mechanism that one can examine how human beings change internally. It defines the ground state that the character begins with and presents a metaphor the character can use to present how the character’s internal state changes—from the point of view of the character. That change is something I am very much interested in.

The interesting character in the original Star Wars three films and the prequels is, of course, Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader. Anakin goes from an innocent boy who loves his mother to a monster and from that monster to a redeemed saint. You can argue the execution was clumsy and the—well, all of the criticisms are valid. We’ll leave it at that.

But the arc is terrific, regardless of how badly it was implemented. Anakin’s corruption from boy to monster does not result from corruption by Palpatine but by incrementally worse and worse choices. Aided by the corruptor, to be sure, but Anakin made those choices. He is a moral participant in the story, not a mindless automaton. What makes those choice interesting is the ground state he begins with—the life with his slave mother—and how he reacts to changed circumstances. As a moral actor, why didn’t he save his mother? What was the moral choice of following the priesthood vs. his earthly duty?

The failure of the films is not the presentation of the arc. It’s the lack of presentation of those internal state transitions.

In The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, Duddy is a poor Jewish young man in Montreal who dreams of being successful. He has a particular image of what success means—landedness—and the story is how he achieves it and the costs to get there. He is less changed by circumstances than he changes himself. The arc of the story allows the viewer to witness those changes. The act of side characters confronting Duddy is the means by which Duddy has to justify himself and justify those changes he decides to make.

Understanding the normal state of the character—the character’s ground state—gives the author the degrees of freedom both in how a person can change and how a person will change. It wraps up the inciting incident with motivation and takes that passive Newtonian object and turns it into a character.

No comments:

Post a Comment