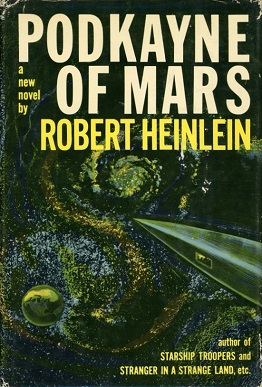

(Picture from here.)

First, let's get a few things straight. Heinlein is not God. Heinlein was a good, if pedantic writer. Like Mark Twain, he liked to pontificate in his work. Like Mark Twain, the quality of his work suffered when he indulged that predilection. Unfortunately, Twain was nine times the writer Heinlein was. Heinlein's later work degenerated into long sermons punctuated by meaningless action and pointless sex.

Podkayne is the story about a young girl about fifteen who has been raised on Mars along with her brother, Clark. Podkayne is fairly intelligent and sophisticated by Mars standards but, Mars being a frontier society, her sophistication pretty much fails outside of Mars. Her twelve year old brother Clark is considerably brighter and much less trusting. They travel towards earth in the company of her Uncle Tom ostensibly for pleasure but later it's known that Tom is on an important political trip for Mars. Things get sticky on Venus. Clark gets kidnapped. Tom gets kidnapped. Podkayne gets kidnapped. Tom is released to do their bidding. Clark develops a plan to escape. Podkayne gets trapped inside the blast perimeter of Clark's bomb.

Podkayne was written in 1962 and published, also unfortunately, in March of 1963-- eight months before the Kennedy assassination. Podkayne, as a teenager, is a late fifties early sixties girl. She wants to be a space ship captain. The pill came out in 1960. Betty Friedan's book, The Feminine Mystique, came out in 1963-- the same year Second Wave Feminism started. Consequently, any radical notions of women working in a man's world (a subtext in the book) were outdated the moment it was published and possibly before.

For example, Podkayne starts out in the beginning of the book all fired up to be a space ship's captain. Later, she admits that it's not so clear she has what it takes since her educational opportunities are limited. She considers marrying a space ship captain as a legitimate alternative to doing it herself. After all, babies are important and fun, too. She doesn't consider bettering the alternatives-- getting help from her Uncle Tom, who is an important senator, or from her possible boyfriend, who is rich beyond belief. In short, there are only two alternatives: slugging it out with a man or sleeping with him. In this, she's a fifties teenager, not the incarnation of a teen at the moment the book is written.

The ending, as published, has Podkayne in the hospital and Clark waiting for her. Clark has some hope of redemption of his sneaky and selfish ways.

Heinlein wanted the book to serve as a cautionary tale for parents that pursue their own goals at the expense of raising their children-- this is the reason for Uncle Tom's diatribe at the end of the book in the original, published ending. In his original, submitted, manuscript Podkayne died. Heinlein thought that having her die validated the rest of the book. The editors thought that killing Podkayne was a downer and had RAH change the ending. Hence, Tom's diatribe so that RAH can be sure we get the right message. RAH said that letting Podkayne live was like "revising Romeo and Juliet to let the young lovers live happily ever after." Which captures both what he thought of the required change and who he liked to compare himself at the same time.

From the tone above you can tell this isn't one of my favorite books.

First, the anti-parenting diatribe comes as a shock. There is no support for it in the book and since it's an add-on I need not respect it.

There are some interesting things going on, however. There's a racial subtext that apparently isn't obvious to a lot of people. I don't mean the obvious statements in the book. Tom is of Maori blood and is dark. Podkayne takes after the Norwegian side of the family and is blond. But there's a subtler, more interesting element. The very fact that Tom Fries is referred to as "Uncle Tom" cannot have been by accident. The scenes describing Pinhead the Venerian are reminiscent of southern white literature depicting black men as rampaging brutes. (See here.) There's also a scene where Podkayne reaches her limit and decides that she's going to plead with her Uncle Tom to do whatever it takes to save her. She's not proud but anything beats being tossed in the cage with Pinhead. RAH wasn't stupid. He knew what he was doing. It's not clear to me what he meant by this but it is clear he meant to something.

Finally, I'll weigh in on the ending controversy.

I read the 1995 version of Podkayne published in 1995. Apparently, there was an essay contest as to which ending was the best. The finalists were listed in the back of the book. Three versions of the ending were included in the book: the original, the first published version and an emended version combining the two.

Largely, the essays fell into "leave the original ending" camp. The biggest reasons seemed to be 1) because RAH wanted it that way and 2) reasons that RAH had given for wanting it that way. The pro essays were largely emotional of the "she's too nice to die" sort. The best essay was that Podkayne had to die because she was too stupid to live. RAH said

Which is close to what I would have said to RAH had he dropped Podkayne into our workshop.

Essentially, all of the essays, the editor and RAH himself were wrong though the "too stupid to live" essay was closest.

Consider the ending:

- Podkayne was out in the jungle with no hope of finding her way back.

- Clark gives her a tracker (essentially GPS) to help her find her way out. She loses it.

- Clark gives her a gun to take care of herself. She loses that, too.

- She doubles back to find a pet she'd left at the compound.

- She then gets lost and circles around in the blast area when Clark's bomb goes off. She dies/not dies depending on the version.

But, like most problems in writing, the obvious solution (leave the original ending) is not the correct one.

It's not whether or not she dies that's the problem. It's the way the situation was set up. RAH set up a condition where her living or dying didn't matter. He had substituted sentimentality for pathos and by doing so made Podkayne pathetic regardless of what happened to her. It's a silly problem and both solutions are by their nature silly. The real solution is to change the problem.

Podkayne doesn't lose the tracker and doesn't lose the gun. She does turn around and goes after the pet. After all, how many pet owners have lost their lives returning to a burning building to save a cat or a dog? She gets the pet and runs outside but there wasn't time. She gets caught in the blast anyway. Perhaps she didn't figure the time well. Perhaps Clark's bomb went off early. Perhaps she bet poorly. Regardless, she was doing something she wanted to do and was caught by the blast doing it, not wandering in the wilderness like some lost and bawling calf.

Now, given that scenario her death (or life) has meaning. So, should she die?

I don't think so.

Forget all the issues of whether she's a role model or is too nice to die. That's all hogwash. What matters is artistic integrity.

For Podkayne to die is artistically sentimental. It's too easy. Podkayne doesn't get a chance to examine her life. (I submit that slogging through bog trying desperately to get away from a nuclear detonation isn't a good time for inner reflection.) She doesn't get a chance to open up her choices and decide her life. Nor does Clark. In either current version, neither gets an opportunity to look at themselves. RAH is giving us easy answers.

The last scene in the book would, of course, when Clark is there with Podkayne, her body burned and broken but with the possibility of recovery, and Podkayne wakes up.

I never liked Romeo and Juliet much, either.

No comments:

Post a Comment